On Friday 14 December, six Eastern SIG members, one ex-member and a potential member all braved the pre-Christmas crowds in Zwolle to enjoy what turned out to be a very jolly ‘happy hour’ gathering.

Despite best efforts by Sally Hill and myself, the table we had bagged and hoped to hold for the group gradually filled with café regulars. This turned out to be a blessing in disguise, however, as we were forced to find extra chairs to ‘expand the circle’ (as in a full-blown traditional Dutch birthday party) so we had no choice but to get even more up close and personal.

The venue – café De Hete Brij – lived up to its fifth place in the Dutch café top 100. Credit to Elles Hetebrij, the owner and creative brain behind this small but gezellig café. I think I can speak for all the attendees when I say it was refreshing to meet and talk with fellow wordsmiths in an informal atmosphere without a pre-set agenda. It’s amazing what a convivial setting and the Christmas spirit can do.

Once the supply of bitterballen had dried up, five of us plus one member’s husband, who joined us later, went in search of a place to have a meal, but could we find a table in the centre of Zwolle? No way. Until someone suggested heading to a shoarma restaurant close by that they'd been wanting to try for a while. And as if by magic, there was just enough space for the six of us. The broad selection of lahmacuns on offer proved to be too tempting for the majority. Washed down with a cool Efes beer, it was just what the doctor ordered.

It must have been around 20:00 when we all went our separate ways – convinced that an Eastern SIG tradition had been born. See you all in February for the next regular meet-up!

SENSE has a number of special interest groups (SIGs) which meet regularly throughout the country. They are open to all members, and guests are welcome to attend one or two meetings before deciding whether they would like to join SENSE. See the events calendar for more details.

The most recent SENSE Ed SIG took place on Saturday 8 December at Park Plaza Hotel in Utrecht, where Giulia Colacicco, a PhD candidate in mathematics, gave a presentation on ‘Contrasting learning methods.’

Giulia gave a demonstration, drawn from her master’s thesis, of a new way to teach mathematical concepts to high-school students. We looked at several videos in which two dots moved back and forth while we were asked to express our perceptions of what we were seeing. More information was added to each successive video, first gridlines, then numbers running along each line.

If you think back to your high-school maths classes, do you remember functions? It turned out the two dots were the values x and y on which a function is based. Giulia reported that this new approach has quite a few advantages. The students on whom she tested her method reacted positively to both the visual presentation of the material and the opportunity to discuss how things worked with their peers. This meant that they learnt together at their own tempo, instead of being individually pressed to give answers. Giulia then presented the traditional equations with which this concept is normally taught, and the contrast was quite striking.

In the second half of the meeting we investigated two ways of learning a language, namely Chinese. This time we did things the other way around. I started by presenting an ‘old’ method – Hugo’s Chinese in Three Months – which I bought back in the 90s. This starts with long explanations of how the tonal system of Chinese works, and builds up (slowly) to words and then a few sentences. Everything was explained in quite laborious detail.

We then switched to the online method developed by Rosetta Stone. Here, no verbal explanations of any grammar or pronunciation points are given, and there is not a word of English in sight. Instead, the student looks at pictures and learns by example. Once a word is taught, it must be successfully picked out from a series of photos on a later page. Grammar is also taught by inference without stating rules.

The attendees certainly seemed to prefer the new method. However, it is worth pointing out that there are no resources such as dictionaries (you have to learn the word and then remember it), one never hears what an extended conversation is like (Hugo’s audio material does offer this) and the method is pretty expensive. What’s more, once your online subscription expires, you lose access to the materials, so you can’t review anything.

Our group had a very enjoyable afternoon, enhanced by the excellent technical facilities offered by Park Plaza’s newly renovated meeting rooms. It is unfortunate that the turnout was so low. Please keep an eye out for the next SENSE Ed SIG meeting, which will be held sometime in May.

SENSE has a number of special interest groups (SIGs) which meet regularly throughout the country. They are open to all members, and guests are welcome to attend one or two meetings before deciding whether they would like to join SENSE. See the events calendar for more details.

It’s time again to put Christmas behind us and get back to work. January is always full of fresh possibilities, and most of us are setting new goals for the year ahead. In this post, we catch up with two members of our SENSE content team – Claire Bacon and Ruth Davies – to find out what they learnt in 2018 and how this influenced their business goals for 2019.

How long have you worked as a language professional?

Claire: I used to work as a research scientist at the University of Heidelberg in Germany. I quit academia and set up my editing business back in September 2015. Now I use my research expertise to help non-native English-speaking scientists get their research published in peer-reviewed journals.

Ruth: I have been editing for around 15 years; before that, I taught linguistics for a few years, working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from all over Australia. I own my sole trader (ZZP) freelance editing business, which I’ve been working in seriously since 2012. I mostly edit research reports in the topic areas of primary production, climate change and remote Australia.

What were your business successes in 2018?

Claire: At the start of last year, my editing business was still a baby. Now it’s more like a toilet-trained toddler that can dress itself. This is all down to the time I invested in editing training last year. I successfully completed three courses run by the Society for Editors and Proofreaders (SfEP) – Copyediting Headway, Medical Editing, and Brush Up Your Grammar – and this increased my confidence no end! It was probably thanks to these qualifications that I was hired by Springer as a copy-editor for one of their biomedical journals. I was recommended for the job by somebody in my professional network (yes, networking really pays off!) and after looking at my CV, they offered me the job.

Ruth: This year was much the same as in previous years, but the conditions were more difficult, so this feels like a success of sorts. I was very busy in 2017 with work, convening the Institute of Professional Editors (IPEd) conference (which was held in Brisbane in September), and then moving to the Netherlands with my partner in October. In contrast, this year has been relatively quiet.

Looking back, I’m most proud of being able to work hard to solve problems for clients, even in tight timeframes. I took the opportunity to do a little more professional development and have done massive open online courses (MOOCs) about grammar (a refresh), social media marketing (new and scary) and corpus linguistics (fascinating). Of course, I also attended the SENSE conference and have had some work through the SENSE forum.

And what lessons did you learn?

Claire: I learnt that continued effort is necessary for marketing to pay off. Marketing is all about making sure that people know what you can do. I’ve started blogging regularly and getting more involved in networking. It took about six months before I noticed the effects. I learnt that you just have to keep at it and that (annoyingly enough) clients won’t find you unless you make yourself visible.

I also learnt how to prioritize. My working time is limited and I realized that something had to give. I stopped doing low-paid editing work for agencies, focusing instead on building my own client base and being there for my children. I also learnt how to say no to people who do not want to pay you the rate you are asking for.

Ruth: First of all, I learnt that a balance is needed between looking for new work, doing voluntary work and doing work. I worked hard on my professional development, but I now realize that if I put the same amount of effort into chasing new work as I did into MOOCs, I’d probably have more work. The same applies to doing voluntary work, which I do for IPEd and for a women’s group I’m a member of here in Utrecht.

Second, I learnt the importance of identifying gaps in production processes. I had a job this year that lasted a long time because the production process went a little awry. While my role was not that of production editor, I should have seen the gap and made sure everyone had all the information.

What are your business goals for 2019?

Claire: I will continue to work on my professional development. I want to learn how to be more efficient with my editing, so will take a course on editing with Word. I also aim to gain professional membership of the SfEP, which will allow me to be listed in their directory of editorial services. For professional membership you need to prove you have sufficient training and experience and you have to provide references, so it really proves your worth as an editor. I also plan to increase my marketing efforts and put more time and energy into developing my blog, which will hopefully bring in more clients.

Ruth: The focus for me will be on building up my client base by putting the social media marketing course I did this year to better use. I’ll also try to use the corpus linguistics method to inform my blog articles for 2019. In May, IPEd will be holding its next conference in Melbourne, so I’ll make that my main professional development activity.

What are your business goals for 2019? Why not share them by posting a comment below?

2018 in review: the year in numbers for SENSE

Written by Marianne Orchard

Utrecht Translation SIG: dealing with challenging clients

Written by Anne Hodgkinson

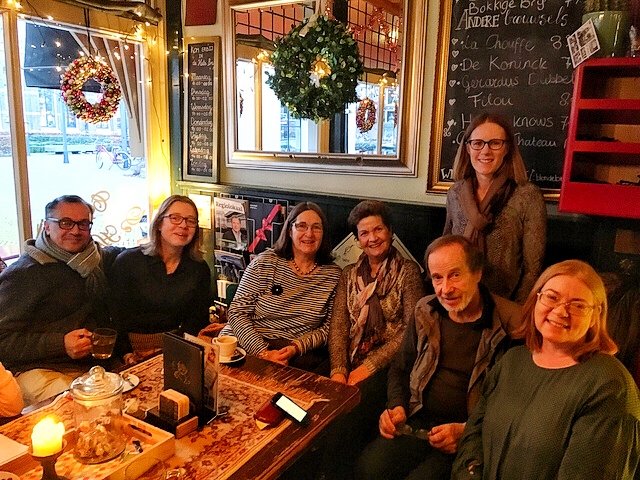

On Wednesday 14 November, 12 of us met upstairs at Utrecht Central station in the Bistrot Centraal to discuss difficult clients. Joy Burrough had been present at similar discussions at the American Translators Association Annual Conference in New Orleans in October and had quite a bit to share, but everyone contributed insights, anecdotes and suggestions to make it a successful evening.

For many translators in other countries, the client doesn’t speak the target language and is ever so grateful that you can help them out. But not here in the Netherlands. Many of our clients speak good (occasionally very good) English, and there’s always one who knows better, having learnt something at school – sometimes something dead wrong – and has to let you know. Many of us had stories to share about these clients. We do need to remember, though, that occasionally the client can be right, especially if specialized terminology is involved. On-line corpora such as Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) are valuable tools in this respect.

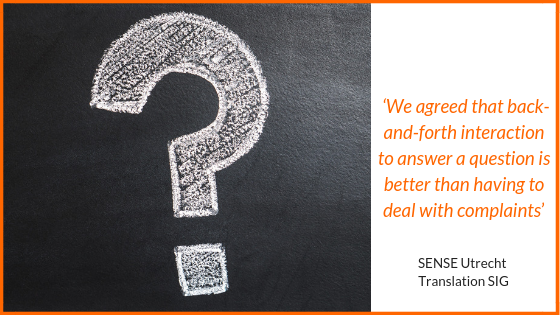

Asking questions

We agreed that back-and-forth interaction to answer a question is better than having to deal with complaints. Most clients are happy to answer questions and like to feel they’re part of the translation or editing process. Asking them what they think of a given suggestion can even help them save face. It’s unusual that you are able to communicate directly with the client when you work through an agency, so you do need to establish early on how any questions will get answered.

The issue of putting comments/questions in the text vs in an email also came up. You need to know if the client is actually going to read your translation or just send it on. Agencies sometimes just pass it straight to their client, and the question you may have asked never gets answered. If you have put questions/comments in the text, it’s a good idea to put something like ‘be sure to read my comments’ in the email when you send in the translation.

‘Correcting’ your translation

Another recurring problem is that someone ‘corrects’ your translation after you’ve sent it in. If it gets published and your name is associated with a bad translation, it can damage your professional reputation. One translator puts a clause in her Terms and Conditions stating that she must be sent the printer’s proofs to proofread and if anything is changed afterwards without her permission, she is entitled to claim €5000 in compensation. How easy – and how costly – this would be to enforce is another matter, but at least it seemed to raise awareness among clients.

Then there is the issue of payment. Sighs all round. Don’t be afraid to be obnoxious if a client is late paying you. If it’s a large company saying ‘we lost the bill’, you can threaten to ask for an internal audit. As with the compensation clause, whether this would work in practice remains to be seen.

Our next meeting will be Wednesday 9 January – stay tuned to the Events page for details.

The UniSIG meeting on 9 November was billed as the first meeting of the academic year, but that wasn’t enough to set warning bells ringing. Even when the introductory round started I was none the wiser: our convener asked me to go first as one of two newcomers in the group of 12. Very nice to get away from my laptop and meet some others in the same line of work, I said.

But were they in the same line of work? It finally dawned on me, as the others introduced themselves, that it was no coincidence that everyone seemed to be doing academic editing. This meeting was aimed at academic editors – whereas I mainly do commercial work. But any feeling of being in the wrong place very soon passed.

Anything and everything

We met in the breakfast room of the Utrecht Park Plaza Hotel, just off the lobby, as the upstairs meeting rooms were still being renovated. It was a busy afternoon at the hotel, but a flip chart was soon trundled over to us so that our convenor could write down the day’s agenda. Officially billed as ‘Anything and everything’, we would discuss agencies offering thesis editing services, whether or not thesis editors should be acknowledged, editing tools and how to manage – and offer – comments.

Writing skills needed

The first topic, commercial agencies helping students with their theses, was prompted by a recent article in the Groene Amsterdammer. Some of these flourishing agencies are apparently now also offering undergraduates help on the writing side, and the article grumbled that their services are a form of plagiarism. Those present agreed that students and scientists at all levels, especially non-native English speakers, have poor writing skills in English. They need help – particularly PhD students who won’t be published if their writing isn’t weighty enough – and few universities offer enough support. A possible niche opening for academic editors, our convener concluded.

To thank or not to thank

This led to the second topic – acknowledgement. With rare exceptions, editors are not acknowledged in academic papers. Ethically, it might seem the right thing to do, but most respondents in the recent SENSE survey on the topic said they didn’t mind if their contributions weren’t acknowledged. One member pointed out that they may not want to be associated with mediocre writing – most authors can’t resist making changes before publication to the version delivered by their editor. Another said simply that he doesn’t need the advertising, while another still leaves it up to the client to decide whether to acknowledge him.

Taking criticism…

This led to a side discussion on what to do about billing to make sure you don’t lose out if editing takes longer because the writing is especially bad. But our convenor managed to turn the focus to topic 3 – how to deal with vague criticism from peer reviewers who don’t accept a version of a paper. The person who had proposed this topic said, ‘They say the English isn’t good enough but don’t go into detail, leaving me guessing what the problem is.’

Asking the journal’s peer reviewers for more information is not an option as they work anonymously, so someone else suggested discussing the situation with the client, which helps build your relationship with them. An alternative suggestion was to arrange for someone else to read the paper and modify it based on their suggestions.

One member said he wasn’t sure if he could charge the client for the time it takes to make such extra amendments, but this was met by a vociferous ‘yes, you can!’ by several people. After all, we cannot guarantee publication. In fact, criticizing the English could be a way for journals to avoid publishing a paper without disclosing the real reason for their decision.

…and giving it

Going off topic only slightly, we discussed what to do with criticism from non-natives along the lines of ‘that’s not English’. These remarks can be hurtful, but it may simply be a case of rephrasing an idiomatic expression or complex construction. One member then handed out copies of some feedback of her own that she had sent to a well-known publisher regarding a poorly translated book. She had agreed to edit it for a certain amount before realizing how much work was involved. Others shared similar experiences. I was reminded to watch out when asked to prepare an estimate based on a short extract. And warned that publishers may seem glamorous but are so cash-strapped they are not good payers.

Editing tools again

The last topic of the afternoon was editing tools. The member who proposed the topic was curious about the PerfectIt workshop on 19 October that a couple of attendees had been to and could report back on. He mentioned liking the subscription version of Grammarly for long texts as it ‘takes out the drab’ and reduces the time needed by the reviewers he contracts for editing services. As well as checking for spelling and grammar, Grammarly looks at consistency, suitability within a certain genre, paragraph length and active verbs. Grammarly flags each item and it is up to the user to decide whether or not to accept the suggested change: luckily, we haven’t been made completely redundant yet.

Right at the beginning of the afternoon, our convenor had asked for questions from the newcomers, but we ran out of time. However, she herself answered one of the questions I had about what might motivate an academic editor: ‘I want to give biomedical students a credible voice so they can go and find the cure for something.’

Marijn Moltzer is a freelance writer, editor and translator for clients including Rabobank, Aidsfonds and Cargill.

What can we learn from our mystery shopper experiments

Written by Tony Parr

Like many others, we recall being first astounded and then fascinated by Chris Durban’s two ‘mystery shopper’ experiments, on which she reported in detail at the 2011 ITI (Institute of Translation and Interpreting) Conference in Birmingham. We decided that we would love to replicate the experiment in the Netherlands, where we live and work. And so we did, adding a number of new elements at the same time. If there is one thing we learnt from our mystery shopper experiment for the 2015 Dutch National Translation Conference, it was that standards in the translation industry in the Netherlands are just as low as they proved to be in France – indeed perhaps even lower.

First of all, standards proved to be low in terms of marketing, where our mystery shopper – a Dutch marketing expert – found it much harder than he had expected to choose a translation agency as they all looked the same. He encountered bland, lookalike websites, meaningless slogans, stock photos and massive and inexplicable price differences. Plus banners brandishing cheap, cheap, cheap, with the occasional ‘quick and cheap’ thrown in for good measure. Standards were also low in customer relations, with shoddy, poorly phrased quotes, a frequent lack of interest in the demands of the job on offer, and minimal customer briefing and debriefing.

Perhaps more shockingly, standards were also low in translation quality, with the translations sold to our mystery shopper proving to be clunky and full of poor collocations, unfortunate phrasing, mis-punctuations, spelling mistakes, typing and formatting errors and – perhaps most damning of all – not even vaguely fit for purpose. This was despite the many extravagant claims made by the suppliers themselves on their websites about ‘working exclusively with native-speaker subject specialists’, producing ‘creative translations’, employing ‘experienced revisors’ and ‘specialist translators from all over the world’ and of course adopting ‘the appropriate tone of voice’.

In assessing the five translations sourced by our mystery shopper, we decided first to ask a panel of three external assessors for their general opinions. Our panel members were less than impressed: three of the translations were dismissed out of hand as being completely unusable, and the other two received mixed assessments.

Perhaps the only morsel of relief for the conference-goers was that the two not-quite-as-bad-as-the-rest translations were also the most expensive ones.

Phew.

We then performed our own detailed examination, marking glaring errors in red, stylistic problems in yellow and nice ideas in green. We allotted points as follows: red = minus 3; yellow = minus 1 and green = plus 2. We were also interested in seeing whether there was any correlation with the cost of the translations in question, so Table A also shows their prices.

As there was not enough time at the conference for a wide-ranging discussion of the implications of the experiment, we organized a follow-up meeting for colleagues from the profession at which they could take a closer look at the translations and debate our findings.

Their analysis of the translations generated two fascinating findings: firstly, the professional translators were broadly in agreement with the original panel of experts. They too felt that the same three translations were worthless and that the remaining two were a mix of good points and alarming weaknesses. None of the translations earned a pass mark from everyone.

Secondly, it was interesting to see that, once the professionals actually embarked on the translation of a short passage from the source text used for the experiment, they soon started asking all manner of questions. Not so much about technical terms as about the target audience and the purpose of the translation. Things like: what exactly does the company want to offer their foreign customers (the source text was a marketing brochure for a corporate events organizer)? Are they planning to organize activities abroad or do they want to invite their foreign customers to come over to the Netherlands? And, which particular foreign markets do they want to break into? Hardly trivia these, but vitally important questions if the translation is to make sense and be effective.

Curiously, not a single one of our original translation suppliers came up with any questions along these lines. True, one of them asked (before starting on the translation) whether our mystery shopper had a preference for either US or UK spelling, and another asked him whether he had any ‘special requirements’. But none of them stopped to think.

Yet stopping to think is exactly what is going to distinguish us human translators from our (ever smarter) mechanical competitors in the future. It was staggering to see that none of our five original suppliers asked for any sort of briefing. None of them called the mystery shopper with questions before delivering their translation. This was despite the fact that we actually asked our mystery shopper to add an extra (poorly formatted) paragraph containing two unnecessary technical details, and various repetitions of points that had already been made. None of our translation providers queried these. Everything was translated simply ‘as is’, including (in most cases) the wonky formatting.

And none of them reported back afterwards to explain what they had done. True, two of them sent a perfunctory ‘How was it for you?’ email, but there was no meaningful engagement at any stage. Indeed, the preferred business model would appear to be: customer chucks a text over the fence; translator translates it as literally as possible and chucks it back over the fence. Quick. Cheap. No questions asked.

We were aware, however, that we were working with a pretty small sample and could hardly claim to have applied much in the way of academic rigour to our experiment. The least we could do was to see whether the situation in the UK differed from that in the Netherlands. So we recently performed a mini-repeat of the experiment for the 2017 ITI Conference in Cardiff. Same text, same mystery shopper, same panel of experts.

What did we find? Well, first of all, it was well-nigh impossible to track down a UK-based translation provider. Despite using a variety of internet search techniques, we consistently found ourselves staring at a hit list consisting largely of global translation agencies and the odd Dutch agency dressed up as a UK operator. Even more surprisingly, individual translators were almost entirely hidden from view: even when our search phrase contained the word ‘translator’, the hits still consisted of agencies.

In the end, we managed to select five potential suppliers for our mystery shopper to contact. Two of them failed to respond to our mystery shopper’s request for a quote. This left us with two ostensibly UK-based agencies and one freelance translator. We say ‘ostensibly’ because one of the agencies proved to be Irish and the other may well have been a one-person eastern-European operation, albeit purporting to be based in a specific English town...

As expected, we encountered the same variety in terms of quality and pricing, except that the range was wider: one of the translations was quite simply appalling (‘Why did you not have a ‘woeful’ category?’ one of the assessors asked), while another was actually much better than the others, including the five we had previously sourced in the Netherlands. The findings are shown in Table B. (Good news for freelance translators: the best translation was that supplied by the freelance translator!)

So, what can we conclude from these two experiments?

1. Four of the eight translations we bought on the open market were complete and utter rubbish.

2. Three were substandard; just one was ‘natural-sounding’, showing ‘good idiomatic choices’ and ‘OK as a first draft’.

3. There was no meaningful customer communication.

4. Agency websites tend to be bland, impersonal lookalikes. They all claim to deliver high-quality products, very often both cheaply and quickly.

5. It’s hard to find individual, professional translators.

If we want to be treated as professionals, we need to act as professionals. That means, for example:

• Doing more than just supplying a passable literal translation, and hence delivering a far more professional product than our clients can get from any mechanical source.

• Communicating with our clients: asking them questions, finding out what they want and telling them what we’ve done.

• Making sure that our clients can find us on the internet and encouraging our professional associations to advertise.

Tony Parr and Marcel Lemmens are professional translators and translator trainers based in the Netherlands. They both have extensive experience as translators (freelance and in-house) and as teachers of translation, principally at the National College of Translation in Maastricht. They are the authors of Handboek voor de Vertaler Nederlands-Engels. Operating under the name of Teamwork, they organize short courses, workshops and conferences for language professionals in the Netherlands.

Jackie Senior

One of the many attractions of MET conferences are the wonderful locations. Girona was well worth the trip – lovely old town, cathedral with the widest nave in Europe and one of the oldest tapestries, numerous good restaurants and bars, and woods and hills within easy reach to walk off the good meals.

One of the many attractions of MET conferences are the wonderful locations. Girona was well worth the trip – lovely old town, cathedral with the widest nave in Europe and one of the oldest tapestries, numerous good restaurants and bars, and woods and hills within easy reach to walk off the good meals.

The 14th annual MET meeting was entitled ′Giving credit where credit’s due: recognition for authors, translators and editors′. Given that this profession is such a self-effacing group, this meeting proved to be an excellent awareness raising exercise. Joy Burrough-Boenisch’s online questionnaire sent out last Spring showed that only 14.5% of us actually expect or ever ask for recognition of our work! How on earth are we ever going to get reasonable pay for our activities if we don’t value our own work? The most common reason given by respondents for not asking for credit was: ‘It has never crossed my mind.’

Thomas O’Boyle (Spain) continued this theme with his talk entitled Knowing your worth, showing your worth in which he urged language service providers to explain to their clients what they do, ensure excellent service and be proactive in seeking credit. It makes sound business sense.

I sat on a panel of academic providers set up by Valerie Matarese to discuss Acknowledgements in the eyes of scholars using language services: perceptions of language professionals. The other participants were Wendy Baldwin (Spain), Kate Sotejeff-Wilson (Finland) and Mar Ferández Núňez (France). Valerie asked us to explain our different work situations, ranging from in-house editor to freelance translator. The questions from the audience revealed the timidity of a lot of language service providers and/or the awe they have for their high-ranking academic clients. It’s worth remembering that professors are just normal people. The panel talked about their own experiences of receiving credit, and offered tips to the audience: the main ones being to pursue excellence, take due pride in your work and start asking for recognition (and not to be put off if one person says no).

On the Thursday evening, I hosted an Off-METM dinner for eight conference-goers to discuss why they wouldn’t want to be credited for their work. Some of the reasons given were: ‘the client may tamper with the text after I return it (and thereby introduce new errors)’, ‘I have been paid, why should I expect credit too?’, ‘I have a list of clients on my website so don’t need credit to be given in other places’ and ‘my client would consider it a loss of face to credit my work because it shows he/she cannot write good enough English’. On the other side of the fence was Iria del Río, editorial director of the official journal of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, which is published in Spanish and English. She explained how hard it is to get any information about the article translators from the journal’s publishers, or to persuade the publisher that credit should be given to the translators.

The conference was a big meeting – 175 participants, with a choice of 13 half-day pre-conference workshops, two or three parallel sessions of talks over two whole days, and 10 Off-METM dinner and 11 lunch groups. The challenge for MET is how to accommodate the ever-growing number of participants while keeping the meeting personal, friendly and so well-suited to language service providers’ needs.

Kirsten van Hasselt

This was my fifth MET conference and, as usual, it didn’t fail to meet my expectations. MET always manages to find the perfect cities and venues for their annual conference. This year was no exception. The wonderful city of Girona, with its many historical buildings, restaurants and great weather, served not only as the ideal place for the conference itself but also as an amazing backdrop for all the Off-METM activities. I attended an Off-METM meal group (for the vegan curious), joined the free walking tour of the historic centre with a great guide, and cycled through the very green outskirts of Girona on a burricleta.

This was my fifth MET conference and, as usual, it didn’t fail to meet my expectations. MET always manages to find the perfect cities and venues for their annual conference. This year was no exception. The wonderful city of Girona, with its many historical buildings, restaurants and great weather, served not only as the ideal place for the conference itself but also as an amazing backdrop for all the Off-METM activities. I attended an Off-METM meal group (for the vegan curious), joined the free walking tour of the historic centre with a great guide, and cycled through the very green outskirts of Girona on a burricleta.

Before the actual conference started, I attended the Translation Revision and Beyond workshop, which was well presented, very interesting and had plenty of interaction. The keynotes and the great variety of presentations were inspiring and informative. And of course, there was the networking. It always feels like meeting up with old friends.

The conference once again gave me lots of creative energy, food for thought and inspiration. Can’t wait for next year’s conference in Split.

John Linnegar

The first keynote speaker was Daniel Hahn, who spoke on In praise of editors: the translator’s view. As a seasoned literary writer and translator himself, he bemoaned the lack of credit given to editors, who, he says, have the potential to either make or break a book. For me, perhaps the most striking takeaway message from this talk, and the conference as a whole, was his Orwellian image of editing being analogous to getting a window cleaned: the view must not be different afterwards (ie, don’t mess with the author’s words and images by imposing yourself on them), but the editor’s interventions must make everything sharper and clearer. He also nicely distinguished the editor’s interventions from the translator’s: editors must help new writers to ‘find their voice’, while translators have to ‘lose their voice’ – the reader should be able to recognize the author’s writing or voice in the translated text.

The first keynote speaker was Daniel Hahn, who spoke on In praise of editors: the translator’s view. As a seasoned literary writer and translator himself, he bemoaned the lack of credit given to editors, who, he says, have the potential to either make or break a book. For me, perhaps the most striking takeaway message from this talk, and the conference as a whole, was his Orwellian image of editing being analogous to getting a window cleaned: the view must not be different afterwards (ie, don’t mess with the author’s words and images by imposing yourself on them), but the editor’s interventions must make everything sharper and clearer. He also nicely distinguished the editor’s interventions from the translator’s: editors must help new writers to ‘find their voice’, while translators have to ‘lose their voice’ – the reader should be able to recognize the author’s writing or voice in the translated text.

For a bit of light relief, I attended Karen Neilson’s presentation on To oak or not to oak… profiling the wine translator. Her message was not about the nuts and bolts of translating in this genre but about steeping oneself in the industry – doing so not only allows one to understand that industry but also means one can provide seamless translation and editing services to its many and varied facets and players: from wine growers to wine tourism. Spain is the world’s third largest producer of wines, but the industry sorely needs a change of image. So while the opportunities for wordsmiths are almost endless, to contribute one has to know one’s stuff, from appellation to terroir. Her final slide in an informative presentation said it all: ‘Get thee to a winery!’

On being edited: how authors respond was the title of Sally Burgess’s presentation. Sally spoke ‘from the heart’ as both an author and an editor. What emerged is that editorial intervention is a sensitive subject for many authors and editors. Developing an awareness of the affective dimension in author editing can therefore improve relationships between author’s editors and their clients. This means that editors must be aware of the factors that influence authors’ positive and negative responses to being edited. In practice, this is about how the editing is framed: an attitude of deference towards the author is more likely to be perceived as solidarity with the author. Whereas, for many authors, having their words edited can be face-threatening, the deferential approach is more likely to be face-saving.

The second keynote having been something of a damp squib for this delegate, the conference ended on an inspiring note with a double bill: Jenny Zonneveld on From Lada to Lamborghini – tips for becoming a premier freelancer and Thomas O’Boyle on Knowing your worth, showing your worth: creating value for your client, creating value for yourself. Not only were the presentations professional but the seasoned speakers were able to speak from experience.

Jenny shared with us the secrets of her success as a freelancer, which included becoming an (indispensable) expert in the field, putting herself through continuous professional development, nurturing networks, building sound relationships and not being afraid to take herself out of her comfort zone (something we language practitioners are notoriously bad at). Jenny also suggested charging a project fee rather than quoting a rate, because it’s difficult to justify higher rates to existing clients. Tom stressed that freelancers should not underprice themselves, because once a rate is set for a client’s work, it’s virtually impossible to increase it substantially. So when quoting a rate for a job, don’t hesitate to start at the right level for you – although this is, of course, easier when working directly for clients than through agencies.

Tom shared seven key words with us: Mindset, Proactive, Improve, Organize, Service, Value and Excellence. These both complemented and added to what Jenny said. Three are particularly important for freelancers: Mindset, which should be that of a business professional, including considering yourself as part of someone’s business, and treating them accordingly; Proactive, which means getting out of your comfort zone to woo potential clients; and Value – adding value to our clients’ businesses (and telling our clients how we do this).

Tom’s final quotation left a lasting impression on me: a client can demand price, time and quality from us, but they need to know that they can’t have all three!

David Barick

This was my third MET conference, and I have found all of them rewarding and beneficial. MET is a very well-organized group and the conference always runs in a smooth and professional manner. The quality of the presentations and speakers is generally excellent. I sometimes hear two complaints: either there is too much emphasis on academic language (according to the translators) or there is too much emphasis on translation (according to the editors). Although I may be at a bit of an advantage since I work in both fields, I personally find the balance between the two very good.

This was my third MET conference, and I have found all of them rewarding and beneficial. MET is a very well-organized group and the conference always runs in a smooth and professional manner. The quality of the presentations and speakers is generally excellent. I sometimes hear two complaints: either there is too much emphasis on academic language (according to the translators) or there is too much emphasis on translation (according to the editors). Although I may be at a bit of an advantage since I work in both fields, I personally find the balance between the two very good.

As it happens, the topics chosen by this year’s keynote speakers were less relevant to my own work than they were in previous years, but I suppose that’s just the luck of the draw. Besides, the MET conference offers good networking, the chance to catch up with acquaintances, and a general sense of camaraderie, all in a sunny Mediterranean setting (the weather was particularly good this year). Another beautiful city – Split, Croatia – has been chosen as the setting of next year’s conference, so my calendar is marked. How about yours?

Joy Burrough-Boenisch

As a freelance editor working primarily for scientists and scholars, I found this year’s MET conference one of the best of the 14 I’ve attended. Here, I’ll mention only the non-plenary sessions I attended but I also enjoyed both the plenaries and fun activities (yoga, burricleta!).

As a freelance editor working primarily for scientists and scholars, I found this year’s MET conference one of the best of the 14 I’ve attended. Here, I’ll mention only the non-plenary sessions I attended but I also enjoyed both the plenaries and fun activities (yoga, burricleta!).

It’s the richness of linguistic resources and expertise among attendees that makes MET conferences so special and rewarding. My pre-conference workshop on editing non-native English, which was again fully booked, attracted 20 attendees with knowledge of 12 languages other than English – including exotics such as Finnish, Bulgarian and Russian but excluding Dutch – so it needed little help from me to draw out insightful comments and discussion. We learned much from each other.

In the conference proper, the panel discussion chaired by Valerie Matarese in which Jackie Senior participated complemented my presentation reporting on the survey of editors’ views on being acknowledged. Jackie’s position (until her recent retirement) as an in-house editor always acknowledged for her work contrasted with the more retiring pragmatic (fatalistic?) approach of the others, all of whom worked for scientists and scholars but were either fully freelance or lacked an appreciative and supportive boss like Jackie’s.

In their excellent joint presentation On being edited: how authors respond, Sally Burgess and Clara Currell (both academics as well as editors) drew on the editing that they’d been subjected to, reminding us not only that editing is a face-threatening act but also to be aware of the hidden agendas of editors, be they jobbing freelancers or – especially – academics who are journal or book editors.

At the other extreme of academic editing, Nigel Harwood’s presentation on ‘proofreaders’ of student texts in UK universities left me with the impression that they are generally neither as skilled nor as foreign-language savvy as SENSE and MET members. His presentation on citation practice in academic texts was useful to me as a teacher of scientific English. This interest was well catered for in two other sessions: Oliver Shaw’s pre-conference workshop in which he showed how genre theory can be used to help scientist authors write (and critically read) the Discussion section of a paper, and Iain Patten’s evangelical presentation in which he advocated integrating research writing into research planning, so that reports and papers evolve with the research, almost writing themselves, rather than being scheduled to be prepared at fixed points in time.

Finally, the six of us attending the ‘Clients who think they know better’ lunch didn’t just pour out woeful anecdotes; we found common experiences across countries as diverse as France, the Netherlands, Spain and Finland, and shared tips on how to avert confrontation and challenges. Therapeutic and fun.

Jenny Zonneveld

This was my third venture to a MET conference, and I’m sure it won’t be my last. The experience is different from any other conference I’ve been to. It’s a belevenis – the city, meeting up with friends and making new contacts, the off-conference activities, the workshops and of course the conference sessions themselves.

This was my third venture to a MET conference, and I’m sure it won’t be my last. The experience is different from any other conference I’ve been to. It’s a belevenis – the city, meeting up with friends and making new contacts, the off-conference activities, the workshops and of course the conference sessions themselves.

MET has a knack for selecting excellent locations where you can soak up the local history and culture as you go along. And now I’ve got to know some of the MET community, I feel very much at home wherever the location.

MET conferences have something for everyone, and this year I selected the sessions on machine translation and business practice. Michael Farrell gave an interesting talk entitled The stink of machine translation – the take-home message being that machine translation will never match the variety, originality or inventiveness of human translators.

My own talk From Lada to Lamborghini was at the close of the conference, and being Spain where food is served at strange times of the day, this began at what we here in the Netherlands would consider after supper time. Despite this, it was well attended and I hope that more people will now dare to venture outside their comfort zone – as I did in giving this talk – to where the magic happens. It will be very rewarding.

Theresa Truax-Gischler

I travelled to the MET conference primarily for anthropologist, editor and translator Susan DiGiacomo’s Friday morning workshop, When the writing is bad but the analysis is good: a practical exercise in editing ethnographic writing, and it remains the highlight for me, hands down. Organized as a seminar, the workshop centred on the editorial analysis of an original draft text of a journal article that had, after revising, been accepted for publication this year in the high-ranking journal, American Ethnologist.

I travelled to the MET conference primarily for anthropologist, editor and translator Susan DiGiacomo’s Friday morning workshop, When the writing is bad but the analysis is good: a practical exercise in editing ethnographic writing, and it remains the highlight for me, hands down. Organized as a seminar, the workshop centred on the editorial analysis of an original draft text of a journal article that had, after revising, been accepted for publication this year in the high-ranking journal, American Ethnologist.

One of the major problems writers across the social sciences have in crafting their work is the effort to bring two very different discourses together into a single, coherent text. It can be quite difficult to bring the highly localized evidence you’ve gathered – whether it be from a village in Europe, a city in Asia, a piece of art, a social movement, a religious ritual or an organization – into the same space as the abstracted and seemingly ethereal concepts and theories within your discipline. Many social scientists obtain reams of fabulous data during their research phase, but then struggle to find a theoretical lens through which to view it. How can you place the unique local data you’ve gathered into conversation with the work of other scholars in your field or those in related areas of critical thought?

To answer this question, Susan presented the best leveraging of Clifford Geertz’s classic ethnographic concepts that I have ever seen. Because ethnographic work in the social sciences is ‘empirical, but not empiricist’, she told us, ‘experience-near’ local knowledge and vocabularies – the raw stuff of qualitative data before it’s been interpreted – must be juxtaposed with ‘experience-distant’ abstract theoretical concepts drawn from the analytic vocabularies of academic specialists. The trick, she explained, is to bring the two vocabularies into simultaneous view such that they ‘vex’ one another and move knowledge forward. In a phrase so pithy that I have tacked it above my editing desk, Susan writes, ‘The intention, as always, is for theory to illumine the data, and for the data to challenge theory, if possible pushing it, and the resulting interpretation, to reach new conclusions.’

The small group of attendees (three no-shows were working on last-minute changes to their own talks) were so moved by the experience of finally having a workshop that speaks to the most difficult elements of editing and translating social science and humanities texts that we organized a Saturday lunch meetup to discuss the possibility of creating a MET Humanities special interest group. Headed up by Sally Burgess of the University of La Laguna together with Alan Lounds of the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya and me (freelance editor Theresa Truax-Gischler), the group’s initial goal is to organize a panel for next year’s MET conference in Split that focuses on the writing, editing, translation and teaching of texts in the humanities, social sciences and literatures. Because these genres are topographically distinct from the genres of the hard sciences, a special stream within MET seemed appropriate. In the words of sociologist Howard Becker, these genres all ‘tell about society’ albeit in distinct ways. As of this writing, the new MET special interest group has 23 members. If you are interested in joining the group, please email me at theresa@nonesuchedit.com.

Curtis Barrett

I’ve been a member of both SENSE and MET since 2011, and even though I’m quite active in SENSE, for the most part I’ve been a bit of a shadow member of MET. But after years of fellow SENSE members asking why I don’t go to the MET conferences, I decided to head to Girona this year to see what all the fuss is about. And I must say, I was extremely pleased!

I’ve been a member of both SENSE and MET since 2011, and even though I’m quite active in SENSE, for the most part I’ve been a bit of a shadow member of MET. But after years of fellow SENSE members asking why I don’t go to the MET conferences, I decided to head to Girona this year to see what all the fuss is about. And I must say, I was extremely pleased!

From the pre-conference workshop on citations, to the meals, to the packed sessions during the conference itself, I found the entire experience engaging and stimulating. Everything was quite smoothly organized, and I found that as a strict non-translator (my core business is editing) there was plenty in the programme to choose from. The location was charming, easy to get around and offered plenty of opportunity to work my muscles trudging up the hills.

One thing that struck me was the way a relatively small conference can have a large-conference feel. During the first plenary lecture, I looked around the hall and saw it was fully packed, making me think that the meeting had drawn around 400 attendees. But later, I asked one of the organizers and was surprised to learn that the actual number was 175.

So to sum up my experience? Thoroughly positive! I’m definitely adding the MET conference to my list of must-go-to events each year, and I’m looking forward to next year’s conference in Croatia. See you there?

Time management tips for language practitioners

Written by Samuel Murray

Following a well-attended informal resurrection in September, the SENSE Eastern SIG (special interest group) kicked off the meeting season on 30 October in Zwolle. Here, Samuel Murray reports on the topics discussed, and adds his own tips and experiences.

For this Eastern SIG meeting about time management for language practitioners, we had all been asked to bring along our top tips. But we were also encouraged to share any problems that we wanted help with – the latter leading to the most lively discussions.

Time management

We learnt that different people have different time-management problems. Some have difficulty starting out or have difficulty getting back to work after taking a break, or find it hard to put down entertainment. Others have the opposite problem – they are workaholics, yearn for a reduction in productivity, and wish that they didn’t accept so many tasks or offers.

While the time-management problems and tips discussed at the meeting were relevant to all freelancers, some were specific to certain tasks. For example, a particular problem for translators is not being able to do editing immediately after translating, but needing to let the translation simmer before getting back to it.

Procrastination

We talked about procrastination in its various forms. Suggestions to address this included the following: if you find yourself putting off starting work in the morning by doing various chores instead, try doing those chores the evening before, or tidying and readying your desk so that the ‘office’ looks more inviting in the morning. Someone else with a problem getting up in the morning had invested in a coffee maker with a timer.

For those of us working at home, if your mind keeps wandering to all the chores you still have to do, it was suggested that we try making an appointment with ourselves for that chore at a specific time of the day. Or to create a physical, visual barrier at the entrance to the office, eg, a curtain, allowing you to leave your house behind when you enter the office, and vice versa.

One member said that she prevents herself from spending time on sites like Facebook by deliberately logging out every time. This prevents her from falling into the trap of ‘quickly checking’ what’s new. Another member used an app that takes a screenshot every minute. At the end of the day, a quick browse through the screenshots reveals which activities were timewasters on that day.

Reducing distractions

Other tips for reducing distractions on the computer included the following:

• if your email program opens automatically on the computer, set it so that you have to open it yourself

• use a separate email address for correspondence that does not generate an income, even if it’s work related (eg, forum notifications)

• to keep your inbox empty, quickly triage incoming email into ‘long reply’ and ‘short reply’ folders that you can deal with later

• make it harder to shift your attention away from work by using a separate browser for non-work related tasks (eg, Chrome for work, Firefox for play)

• regard anything that doesn’t help bring in money as entertainment!

Keeping clients happy

Some people struggle with communication-related tasks that form part of being a freelancer but do not specifically generate income. An example is when you spend time trying to help out a potential client by arranging for an alternative translator or editor from your network, or when you spend time writing a careful reply to something that you know for certain won’t lead to work, because you want to be polite and/or helpful. Although no concrete solutions for this were forthcoming, we agreed that helping clients and colleagues is indirectly good for business!

We also discussed the issue of accepting jobs over the weekend. Someone suggested that if you find a lot of your work comes in on Friday evenings or weekends, you could try having your ‘weekend’ on other days, eg, Wednesday and Thursday. I myself tend to compromise by trying to keep my Friday afternoon and Saturday free, and then start working again on Sunday at noon, rather than working on Saturday in-between other activities.

Also, I find that if clients want work done by 9:00, I try saying I can do it for 14:00, which gives me that extra bit of time in case something happens. In line with this, others agreed that if the work has tight deadlines, we should not accept assignments that fill our hours to the maximum (per client) but try to negotiate deadlines that allow us to have gaps in our day, which can then also be filled with work for other clients. Similarly, when setting up my out-of-office reply, I am generous with my estimate of when I expect to return in case I end up running late – especially handy for those clients who expect instant replies!

Technology: help or hindrance?

Technology in various forms was of course discussed. Firstly, for those distracted by sounds, listening to music can help us concentrate and it was interesting to hear that we preferred widely different types of music – from relaxing instrumental music to heavy metal to something in a foreign language.

In terms of software, while most time-management problems can’t be solved by simply downloading an app, a number of members reported success using Pomodoro type apps. The Pomodoro Technique dates from the 1980s. It involves alternating between short productive sessions and even shorter rests, and turning small tasks into goals to avoid procrastination. The original system used a notebook, pen and kitchen timer, but apps make it easier to set goals, tick off achieved tasks and stick to time intervals.

One particularly popular app that can be combined with the Pomodoro Technique is called Forest, which involves a game of planting and caring for pet trees to help visualize how much you can resist the temptation to switch to other apps.

The browser-based version of Forest (for Chrome) allows you to continue using your computer and browse the web, but penalizes you for visiting certain websites such as Facebook and Twitter, or any other site you add to its blacklist. One can also combine the smartphone app and the browser app into a single system by logging in.

All in all, I found this to be a very productive meeting. It was great to hear that other freelancers sometimes struggle with similar problems, to learn how different personality types or lifestyles lead to opposite types of problems and to hear feedback on our time-management problems from different perspectives.

SENSE has a number of special interest groups (SIGs) that meet regularly throughout the country. The Eastern SIG, which meets in Zwolle, gives people the opportunity to speak English with one another and share experiences about professional practice and life in the Netherlands. SIG meetings are open to all members. Guests are welcome to attend one or two meetings before deciding whether to join SENSE.

Samuel Murray is an editor and translator (English-Afrikaans) who specializes in health, medicine and information technology.

Samuel Murray is an editor and translator (English-Afrikaans) who specializes in health, medicine and information technology.

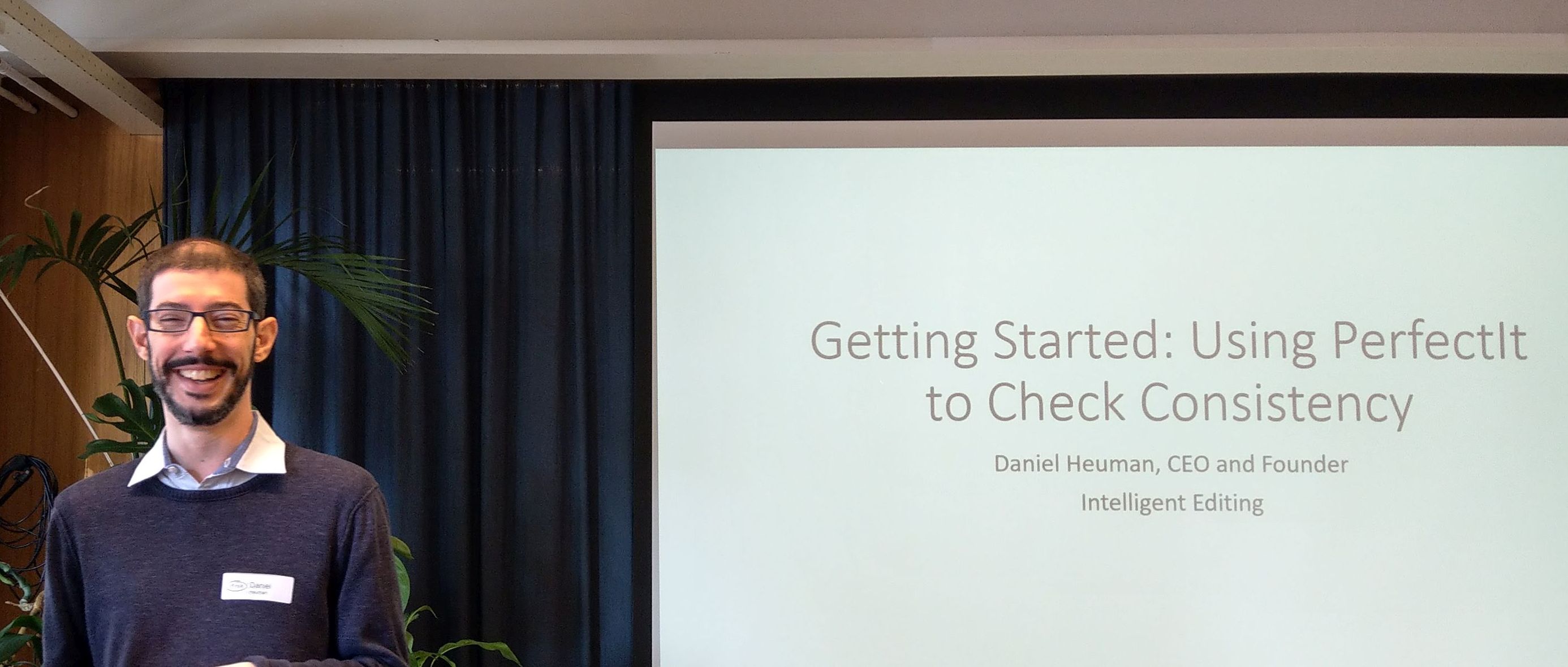

Like many of you, I am already a PerfectIt user. I love to do a PerfectIt pass after I’ve edited a document and fix all those contrary hyphens and stray capitals. I’ve been meaning to do a course for ages (or actually read the documentation or watch the videos). I think I may have done the introductory one when I first downloaded the software in 2014, but I haven’t been back to the website much since then and … you know.

So when I got an email from SENSE saying that Daniel Heuman, the creator of PerfectIt, was going to a deliver a course here in Amsterdam, I signed up.

For those who don’t know already, PerfectIt is an add-on to Microsoft Word that checks for consistency and enforces style. It is not a grammar or reference checker. PerfectIt leaves each decision to the editor, so you always have control over changes being suggested and made.

Daniel developed it for consultants working on long reports because he knew from his previous job how difficult and time-consuming these fiddly things are to find. Daniel says it took him six months to realize that editors are a key market. Who would have guessed that we editors even care about details?! At any rate, it’s now almost ten years later and PerfectIt is also being used by professional translators, government institutions, universities, the European Space Agency – it’s an impressive list of clients.

After that background, the workshop was split into three sessions: beginner, advanced and Daniel’s other favourite software picks for editors.

In the beginner session, Daniel showed the recently released Cloud version, which can be used on Mac and PC, and he walked us through some of the tests PerfectIt does. I’ve become so used to it that I had forgotten how amazed I was the first few times I ran it over a document and it picked up all those ‘broad-acre’ and ‘decision making’ instances when I wanted ‘broadacre’ and ‘decision-making’! It is much faster than me having to manually check for these.

PerfectIt also has a bunch of functions I haven’t used, particularly those at the end of a pass, such as generating a report of changes and compiling the comments in a document. I also didn’t know if it could check just part of a document, so I gave it a test and sure enough, it asked me ‘Do you want to check only the selected text?’

In the advanced session, Daniel talked about enforcing style manuals. PerfectIt comes with a number of built-in styles such as Australian Government Style, United Nations Style and US Spelling. You can either use these styles as they come or make copies of them to tweak. For example, I use UN style for one client, but they like ‘program’ instead of the UN’s preferred ‘programme’. In this session we went through the tabs in the ‘Edit Current Style’ function, which was a great reminder to me of how much control I have over all the tests PerfectIt runs.

Daniel also talked about using PerfectIt’s wildcard check which makes some tests very powerful and much faster because it searches for patterns of text, rather than individual instances. For those unfamiliar with wildcards, he recommended Jack Lyon’s Wildcard Cookbook which is available for free here.

The company that sells PerfectIt is called Intelligent Editing and their website has 10 online video tutorials, ranging from between about two and five minutes long, that talk you through PerfectIt’s functions, ranging from between about two and five minutes long. I’ve already had a look at one to remind me how to do something I saw in the workshop.

In the last part of the session, Daniel shared with us a range of other tools that he thinks are helpful for editors. Daniel recommends trying a new piece of software every few months – you’ll keep learning, and you could well find a tool that revolutionizes your working day. He suggested a variety of software to include in such try-outs, although not all are available for both PC and Mac and not all are free. But I’m providing the links here so you can have a look at them.

| ClipX | Creates a system-wide clipboard that holds 25 items; no more going back and forth to paste things between applications! |

| WordRake | Simplifies complex writing; very handy to turn text into plain language. |

| TextExpander | By using shortcuts, lets you quickly insert boilerplate text. |

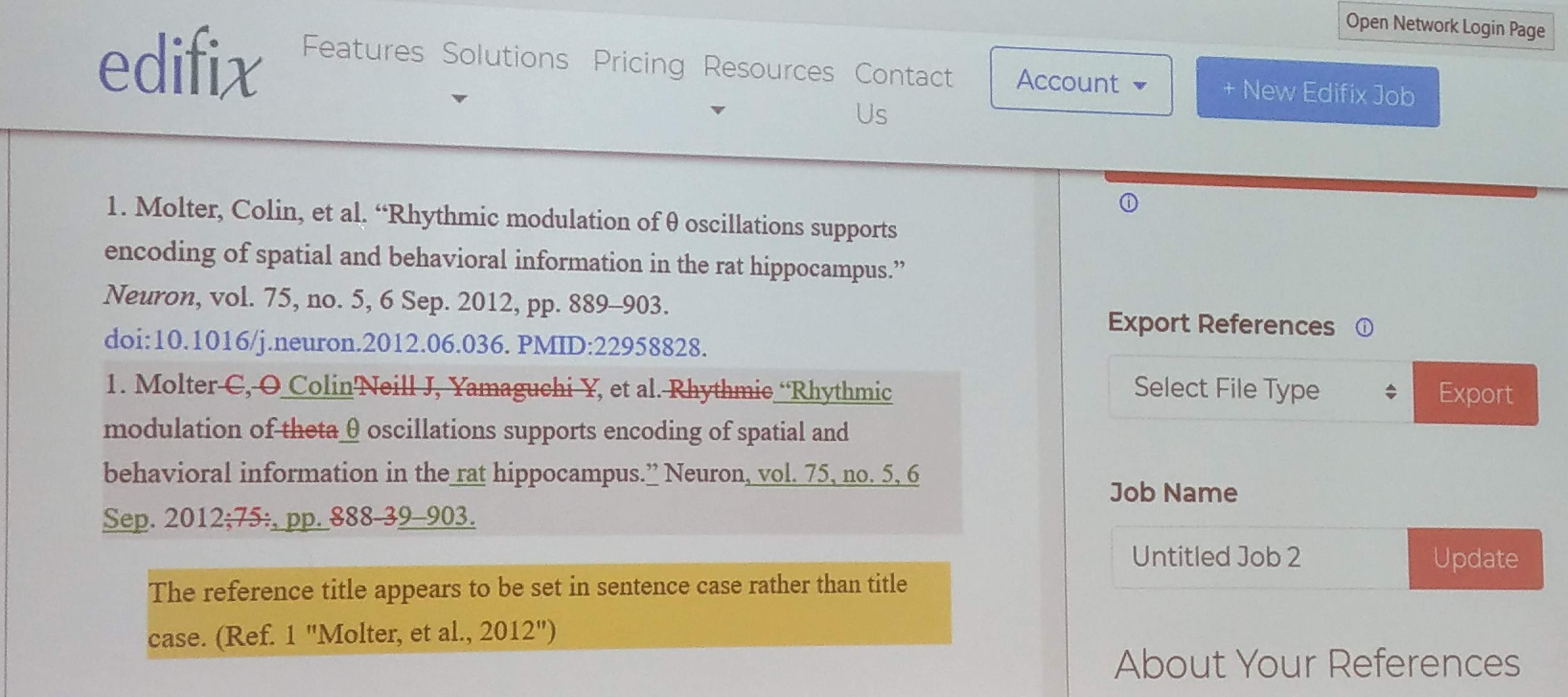

| Edifix | Fixes reference lists by looking for the citation in Cross Ref; super, but expensive. |

| File Cleaner | Corrects messy documents and fixes common typesetting problems. |

He also mentioned other programs (Stylewriter, Editor’s ToolKit Plus) and concepts (use macros, wildcards and shortcut keys in your work).

I’d been meaning to do such a workshop for a while, and I’m so glad I did. It gave me confidence to know that I’ve mostly been using PerfectIt the way it should be used, but also reminded me how I can take more control over style sheets for individual clients. There is a Facebook group called PerfectIt Users, and I think I’ll be able now to contribute to that rather than just lurking, as I have been.

Ruth Davies is an Australian freelance editor currently living in the Netherlands. Through her business centrEditing, she edits research reports about all sorts of interesting things, including climate change, remote Australia, and agricultural development in Africa. She joined SENSE at the beginning of 2018.

Ruth Davies is an Australian freelance editor currently living in the Netherlands. Through her business centrEditing, she edits research reports about all sorts of interesting things, including climate change, remote Australia, and agricultural development in Africa. She joined SENSE at the beginning of 2018.

For more information on the recently released Cloud version of PerfectIt, take a look at Michelle Luijben-Marks' review here on the blog.