[PDD 2021 session recap] Intercultural business communication

Written by Rebecca Reddin“How I had learned to communicate was different than the style used where I now was”

In her two-part panel discussion during the first SENSE Professional Development Day, Nandini Bedi made us aware of our communication styles. Her presentation revealed how style is a fundamental part of cross-cultural discourse. The styles we use and encounter as linguists are diverse, and we need to keep that in mind as we dialog and write.

When speakers use inductive communication, listeners are responsible for discerning the message. They must pick up on hints and patterns as the speaker gradually reveals their main idea. Nandini took her example from English textbooks, which position target structures within a text. After making sure students have understood the general idea, the structure is highlighted so students will notice it. Lastly, how the grammar works is finally explained. The textbook moved from general to specific, indirect toward direct.

In contrast, speakers who use deductive communication state their core message up-front, only filling in details and context as the narrative goes on. Deductive communication is the standard for academic articles written in Western scientific tradition. An introduction or abstract gives readers the main idea, and more details and context are eventually provided in the text body. Deductive communication makes the speaker responsible for comprehension. They must pre-empt any questions recipients might have.

Nandini emphasized that each communication style is nothing more than that: a style. Every style has advantages and pitfalls, and any style can leave their audience lost, especially if speakers don't share the same one. For example, inductive communication might seem evasive to deductive communicators, and deductive communication could feel rude to inductive communicators.

Our preferences for a given style reflect the communication patterns we acquired at home, at school, and at work. In other words, our cultural backgrounds are good predictors for the way we interact in the world. High-context cultures such as India encourage detailed context-giving. Nandini explained that explicit politeness strategies (which often adds to the length of interactions) are key to navigating highly stratified societies. Deductive communication has more social currency in low-context cultures such as Dutch culture. The Netherlands are more socially homogenous than India, Nandini pointed out.

Like languages, we can either acquire or learn our communication styles. The key to success is knowing your purpose and your audience. Nandini emphasized that when we speak, we must put ourselves in our interlocutor’s shoes. We need to think about how they will receive our message, and the method we choose should correspond to how well our idea will be received.

Nandini’s presentation was a wonderful reminder to be mindful of others' expectations for interaction. Following the formal presentation, attendees shared personal accounts of cross-cultural miscommunication. The crux of each example was invariably rooted in cultural assumptions. As professional communicators, we inhabit the spaces between our clients and their audiences. It is our responsibility to mind the gap and leave a footprint that anyone on the other side will recognize.

8 October UniSIG meeting report: Prof Nigel Harwood on proofreading students' texts

Written by Joy Burrough-Boenisch, Jae Evans, Jackie Senior

Nigel Harwood, now Professor in Applied Linguistics at Sheffield University, is no stranger to SENSE. In 2014, when we were developing SENSE’s Guidelines for Proofreading of Student Texts, he and Liz Austen came to talk to SENSE about their research on proofreading practices at Essex University and that university’s policy and guidance on proofreading. At the SENSE conference in 2018 he presented his findings on proofreaders’ interventions in a Master’s text, and now he gave us an online presentation on The ethics of ‘proofreading’ at UK universities and reported on his recent study into students’, lecturers’ and writing tutors’ attitudes to proofreading practices.

Nigel explained the outcome of his recent research, which was driven by three questions:

- How far do university content lecturers, English language tutors and students feel it is ethically appropriate for proofreaders to intervene in students’ writing?

- Why do lecturers, tutors and students feel the way they do about the ethics of the various proofreading interventions?

The term 'proofreading' was used to cover a range of interventions including minor/major copy editing, structural editing, content editing, indirect editing, and no intervention. SENSE members raised queries about the definition and Nigel clarified that his terminology was based on his own work and that of Brian Mossop (York University, Ontario). Nigel’s definition – quoted in SENSE’s Guidelines – confines proofreading to student-authored texts by stating that it concerns making changes to ‘assessed work in progress’. After reminding us of this careful wording, he noted that it doesn’t apply to the practice in the Netherlands and elsewhere in mainland Europe of helping PhD candidates achieve publishable articles for their thesis.

Nigel’s study involved lecturers, EAP tutors and students (122 in total). The vast majority in all three groups were in favour of some form of proofreading. Unsurprisingly, students took a more permissive stance, with most approving of proofreading intervention. Lecturers and tutors took a less liberal view and voiced concerns about how proofreading interventions might affect student grading. Nigel explained that some lecturers believed that proofreading interventions should not be allowed where language usage and accuracy was being explicitly graded. Conversely, if the language was not part of the assessment criteria, why would the student need proofreading intervention? If the message and ideas were communicated adequately, especially in the case of multilingual authors, then the lecturers were satisfied: language accuracy was not an issue.

To put the results into perspective, Nigel elucidated the findings from the two extreme outliers among the lecturers. The ‘ultra-permissive’ lecturer believed that accessing proofreading intervention was completely acceptable and played a role in inclusivity. Nigel explained that while some students may have access to university-educated parents and well-educated networks they can turn to for proofreading and feedback, access to support via proofreaders and academic editors was a form of equality for those less fortunate. The extreme opposite – the ultra-non-permissive lecturer – believed that no intervention should be allowed, with an inference of cheating. Nigel contextualised this viewpoint by saying the assignments set by the non-permissive lecturer included assessment criteria for language accuracy. Summing up, Nigel pointed out that there was less agreement among the interviewees on how far proofreaders should be permitted to go. His three recommendations on how universities might safely authorise proofreading were to ‘permit only a lighter-touch version of proofreading which eschews content interventions; regulate proofreading by taking it in-house; and allow departments to permit or prohibit proofreading from assignment to assignment, depending on assessors’ aims, outcomes, and assessment criteria.’

One recurrent theme from the research was that ‘proofreaders’ (as defined in Nigel’s research) should not be commenting on or adjusting content. He did concede that some lecturers accepted comments and questions from the proofreader to prompt the author to consider faulty argumentation or missing information. This type of intervention is referred to as ‘editing for educational purposes’ by some universities.

In wrapping up his presentation, Nigel remarked there was still no consensus on how much intervention is acceptable. Some UK universities ban proofreading altogether, whilst others take a non-committal stance. Sheffield University, for example, has placed a blanket ban on proofreading but all students (English native speakers and international) are entitled to six hours of advice from the English Language Teaching Centre. One solution suggested by Nigel was to have ‘in-house’ staff to support academic writers through the university writing centres. However, this would not satisfy university staff who believed any intervention to be unethical and could lead to a return to unseen assessments.

Nigel’s presentation was enlightening and provided a clear message about the perspective of UK universities. We are grateful for Nigel’s time and look forward to hearing from him in the future about other EAP research interests.

[PDD 2021 session recap] Spanish wine and translation: what could they possibly have in common?

Written by Anne Hodgkinson

I attended Rebecca Reddin’s session on PDD day 1 (repeated on the second day) feeling ready to be entertained. After all, I like both Spanish wine and translating, although I have had some disappointing experiences with both as well. For me, one major difference is that one costs money and the other brings it in. However, many of Rebecca’s clients are Spanish winemakers, so hopefully she’s found a balance.

Once Rebecca got started, the parallels seemed fairly obvious: both Spanish wine and translation are cultural products, influenced by factors like geography, history, social function and values. Both are ancient human pursuits and thereby have respected traditions associated with them. Using corks is one good example from the wine world. Although there is an argument that corks are cheaper if you’re already near the cork-oak trees, wine corks are hallowed tradition in Spain. Spanish winemakers wouldn’t be caught dead putting wine in screw-top bottles. (Or at least not selling them in Spain; one SENSE member has seen the same Rueda with a cork at Spanish supermarkets and in a screw-top at Albert Heijn.) With both wine and translations, a good end product requires time and good raw materials, such as soil/sun/vines and in our case, the source text. There are different styles; wine has different colours, grape varieties, etc. and translations come in different types of text, voices, etc. And both entail continual decision-making along the way.

But this was just the beginning. The above points were only from one perspective, ‘looking from the inside out’, ie, from the point of view of people inside each industry. She continued her analysis ‘from the outside in’, ie, from the perspective of people not involved in the industry in question. Both winemaking and translating are opaque processes to most outsiders. Most clients aren’t aware of how the finished product happens. Clients don’t always care about this either – for most, the only question is whether they like it or not, and not necessarily why they like it. The price/quality relationship is another aspect the two share. Lastly, in both industries client trust often has to be established first.

Moving on, she mentioned changes such as market trends, social and cultural shifts, and new technical/technological developments as factors that neither field can ignore.

In closing, Rebecca offered some lessons to be learned. Firstly, speak your client’s language, not yours – our clients may not want to know about the percentage of matches or the passive voice any more than people buying wine want to know about malolactic fermentation. Secondly, your image is also something that matters to the client (see corks above), even if your product itself is something they can’t really see. Thirdly, focus on a segment of the market that you resonate with. And lastly, collaborating with others can sometimes bring about some exciting results.

So in fact the translation world and the Spanish wine world are not all that different! This was an entertaining and thought-provoking session. It ended at 12:20, which in Spain was probably time to knock off for lunch and a glass or two of wine, but for me, time to get a little more coffee before the next session…

In her previous two articles on quoting for jobs, first published in eSense, Sally Hill discussed how to quote for translating and editing jobs. In the final part of this series from 2016, Sally turned to copywriting jobs.

In a 2016 thread on the [members-only] SENSE forum, members provided useful advice on how to avoid exceeding an estimate for an editing job. Many of us have been in similar situations and it serves as a reminder that taking the time to prepare a quote that anticipates any interim changes or unexpected situations can save you headaches when it comes to invoicing – whatever the job concerned.

What do we mean by copywriting anyway?

For starters, it’s probably handy to define what we mean by ‘copywriting’. In Dutch, a tekstschrijver is not necessarily the same thing as a copywriter since the latter is often considered to apply only to advertising texts. Indeed, Wikipedia confirms for me that copy is ‘a content primarily used for the purpose of advertising or marketing’. So while in Dutch the distinction is easily made, in English there is apparently no term other than ‘writer’ for someone employed or contracted to write texts other than those intended for advertising. In fact, when completing one’s profile for SENSE, the only kind of writing service we can select is ‘copywriting’. I myself have recently started doing some medical writing, which sees me working together with biomedical scientists at a biotech company to write internal scientific reports – a far cry from advertising or marketing. So it would appear that, within SENSE at least, the term ‘copywriting’ includes a broad range of writing assignments.

And what kinds of texts are we talking about?

A brief survey of a handful of the many copywriters in SENSE reveals that clients employ freelancers to write a wide variety of texts. These include brochures, internal corporate texts, conference reports, policy documents, interviews and other articles for company magazines, as well as website texts and expert blogs. SENSE also has a copywriting special interest group (SIG) and a glance at the topics discussed at their meetings tells me that writing for the web is a much-discussed item.

Can you write a brochure for us, Sally?

But let me tell you about my own experience quoting for a copywriting job. Back in 2012, the European Platform (now EP-Nuffic) asked me to write a 5000-word brochure on TTO (tweetalig onderwijs or bilingual education) in Dutch schools1. Since I’d been teaching at TTO schools for several years and had presented at a TTO conference, I was the ideal person for the job they said. They were not put off by the fact that I did not actually have any experience with copywriting; what they needed was a native speaker who understood the system from the inside who could help explain TTO to teachers in other countries. Welcoming the challenge, and not averse to a spot of writing, I accepted the job. But of course they needed an idea of what I would charge – which is where I hit a brick wall and turned to SENSE for help.

SENSE to the rescue

I posted my Forum question on how to estimate the time it would likely take me to write this brochure and SENSE members were most helpful. Although I’d heard somewhere that 4.5 hours per page (100 words an hour?) was a good starting point, I was advised that copywriters never quote in terms of length of finished product (per word or per page) but rather per hour or per day, since the job rarely involves just sitting at your desk thinking up text. Indeed, I would also be meeting up with the client to go through the content, and be setting up and conducting several phone interviews. So the thing to do was to come up with a unit price for each quantifiable part of the job (per meeting or interview) and another for the unquantifiable parts, i.e. X hours of research, Y hours of writing and Z hours per revision round; also bearing in mind that I was likely to underestimate each part and take this into account by giving a range for the total number of hours. This worked out well in the end: thanks to SENSE-ible advice, I raised my original naïve estimate of 28 hours up to 40 hours, which the client was happy with. Although I’ve not been asked to do anything similar since then, the experience did give me more confidence when quoting for courses and workshops, for which I also need to break down the costs involved.

Break the costs down

So a quote needs to include a list of things that you expect to be doing (such as meetings, phone calls, research, interviews, writing, revision rounds) and an estimate of the hours needed for each item, plus expenses such as travel costs and travel time if applicable. Then you need to state what is not included in the quote, what will affect the numbers of hours needed and when you can deliver by (see example below using a template from the internet; click image to enlarge).

If applicable, I often also state anything the client has agreed to provide me with, and by when, so that it’s down on paper that they must also meet their side of the bargain! For some of his clients, my graphic designer husband even requests a signed copy of the quote be sent to him by post before he’ll even start a job.

These kinds of breakdowns are not always needed though. If you do repeat jobs for the same client it may be more useful to have a fixed price for a press release, or a certain type of article, or a rewrite, with some jobs taking longer than others but averaging out about the same.

It’s in the details

In terms of how long the actual writing part takes, various people have given me their rule of thumb, which ranges from 75 to 200 words per hour. But of course this can depend on so many different factors, including the complexity of the topic, how familiar you are with it, and how much research you’ve done before starting the actual writing. In terms of hourly rates, SENSE’s 2012 rates survey indicates that these vary from €30 to €110 for copywriting. Finally, a factor that should also be considered when putting together a quote is how badly you want the job! After all, topics or clients that are appealing to you may reduce the amount you quote, whereas those that are unappealing may raise it. High-quality clients who pay on time, no questions asked, may well save you time and money in the end. More information on rates, pricing and other resources for copywriters can be found on the website of the Professional Copywriters’ Network in the UK.

And this concludes my three-part series on quoting for jobs. I hope I’ve managed to cover the majority of aspects us freelancers should consider when tackling this tricky task. If not feel free to get in touch and let me know. My thanks for this final article go to SENSE copywriters for their input, including Martine Croll and Carla Bakkum.

1 A PDF version of the finished product, ‘Bilingual education in Dutch schools: a success story’ is available for those wanting to read more.

|

Blog post by: Sally Hill LinkedIn: sally-hill-nl Twitter: SciTexts |

[PDD 2021 session recap] The freedom of freelancing

Written by Yuven Muniandy

Have you ever wondered if it is feasible to work wherever you want to? Is it even possible to travel and build your business? Maaike Leenders answered these questions on digital nomadism and more at the 2021 SENSE Professional Development Day. After working in-house for almost five years, Maaike exchanged her office for the open road and has taken every opportunity to lead a digital nomad lifestyle. Based on her personal experience, she offered practical tips for beginners interested in becoming digital nomads.

Maaike started her presentation by dispelling some common myths associated with the digital nomad. Many think of digital nomads as young, attractive people working on laptops on picturesque islands like Bali or Crete. The problem is, this beachy, chill lifestyle is often confused with the wider concept of working remotely. According to Maaike, a digital nomad is a person making a living by working outside the conventional office environment, for longer or shorter periods at a time. They use the flexibility of their online career to travel and expand their horizons. Therefore, it is certainly not a life-hack that means you never have to work again. Additionally, this lifestyle is not everyone’s cup of tea.

Now that it’s clear what digital nomadism is not, let’s look at how one can become a digital nomad. First, we must ask “why do we want to pursue this niche?” and start a career as a digital nomad. There is more to life than work: family, friends, health issues, pets, and social responsibilities. These considerations lead to other questions: ‘how much do you want/need to work?’ and ‘how much you want to travel?’ Once these questions are answered, we are almost ready to say ‘sayonara’ to our old work lifestyle. It is vital to build up a cushion of money (cash buffer) to fund your start-up costs. It is also crucial to clear any financial arrears. Outstanding debts may be the barrier to becoming a digital nomad for a long time.

Other practical tips highlighted during the talk were related to income, ergonomic workspace, and having proper internet connections. Digital nomads often work for clients outside the time zones they travel to. Hence, it is necessary to organize your time to meet client needs. Like any profession, digital nomadism has its highs and lows. Maaike highlighted that it is important to be mindful of our emotions when we are earning a living as a digital nomad. Loneliness and homesickness are common emotional setbacks. Creating your own definition of freedom and learning to say ‘no’ are important for a balanced business and personal lifestyle.

At the end of her presentation, Maaike suggested resources that offer tips on how to travel and earn at the same time. These include books, Facebook groups, and volunteer organizations. There are also some excellent platforms for homestays, such as WWOOF, WorkAway, and HelpX. These platforms offer opportunities to stay abroad without paying ridiculous amounts of money. A take-home message from Maaike’s presentation is that everything always works out, even if it never goes according to plan. And that it is often better to start small.

In the first part of her 2016 Best Practice series for eSense, Sally Hill talked about quoting for translation jobs. Here on the blog we are also re-publishing part 2, which continues the theme in relation to editing jobs. This article first appeared in eSense 42 (2016).

Before I get started on how to quote for editing jobs, let me touch on the thorny issue of the different levels of editing. After all, what I do as an editor may not be the same as what other editors in SENSE do, and this will of course affect the rate we charge and the time it takes to edit a text.

What do we mean by editing? What does the client expect?

In their chapter of the SENSE Best Practices Handbook entitled ‘The Ins and Outs of Editing’, co-authors Lee Ann Weeks and Ann Bless make the important distinction between ‘editing’ and ‘editors’ as referred to in the publishing world and the terms as used by most editors in SENSE. They also set out the difference between ‘proofreading’, ‘copy-editing’ and ‘substantive editing’, or what is generally understood by these terms. They use ‘proofreader’ to refer to the person who ‘compares the penultimate version of a text (ie, copy) with the final typeset/formatted version of the text (ie, galley proofs, page proofs, uncorrected proofs).’ This is similar to the definition used by the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading [formerly known as The Society for Editors and Proofreaders, ed.] in the UK. Their website provides useful information on the distinction between copyeditors and proofreaders. A useful rule of thumb the CIEP provides is that a proofreader does about ten pages (some 300 words per page) an hour. If what you do takes considerably longer, you are probably copyediting and not proofreading. But ‘proofreading’ is also used in other contexts and I discuss this a bit more below.

You should be aware of the level of editing that you offer – and of course inform your clients of this. For new clients you could offer to edit the first page or so for free so they know what to expect. I sometimes include a sample edit with my quote so the client knows what they will be getting for the amount quoted. A client just expecting corrections regarding grammar, spelling, syntax and consistency (what I call language editing) may not appreciate me changing sentences around or commenting on content. As an editor used to substantive editing – and particularly used to educating PhD students while editing their work – I find it hard to limit myself to just language editing. If a new client asks me to do so I pass on the name of a colleague. For more on sample edits, see this forum discussion.

Or is what I do proofreading after all?

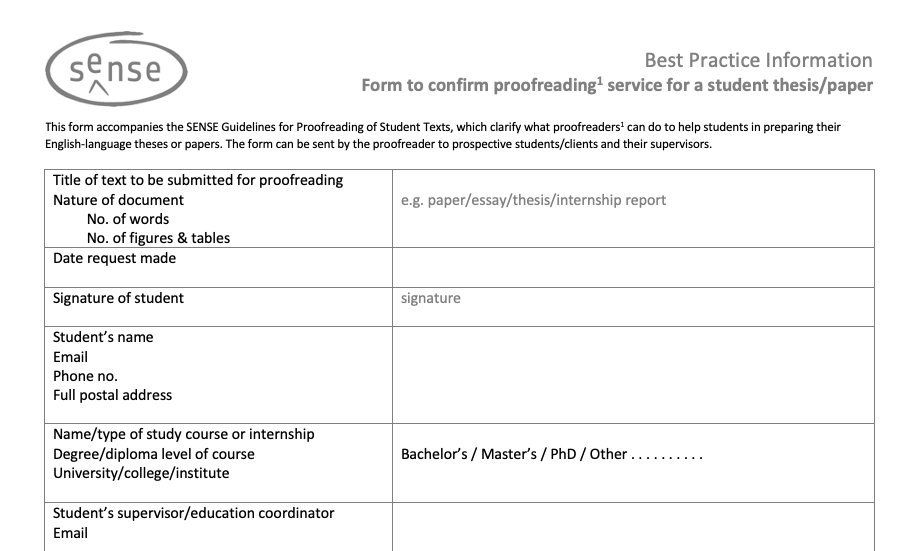

If you are more of a fixer and a flagger, then the other type of ‘proofreader’ may be a term more applicable to what you do. And if you proofread student manuscripts and PhD theses then you are also in luck – the SENSE Thesis Editing Guidelines developed by SENSE’s special interest group for members working in academia (UniSIG) are available on the website. They include such useful items as suggestions for acknowledgements and a form to clarify the help editors provide to students. In these guidelines the term proofreader is defined as ‘third party interventions (that entail some level of written alteration) on assessed work in progress’.[1]

So I know what I do but how long will it take me?

This is one of the hardest things about being a freelancer and a sample edit can really come in handy. For me, when a new manuscript comes in I can now estimate from the length and the quality of the English how long it will likely take me to edit it. But when I first started doing this work, I would edit one or two pages and time myself before getting back to the client with a quote. Sometimes this would backfire if the quote was too high and the client went elsewhere, but I learned quickly to quote a range. I tell clients that it may take me less time than the number of hours indicated but it will not cost them more than the maximum quoted, even if I go over the maximum number of hours (my loss). And when I find myself going off on tangents while editing a text that is just too interesting – when the time I spend on research (eg, reading up on certain molecular pathways or surgical interventions, or scanning other publications to see how other authors use certain terms) exceeds that strictly needed to edit the text – I do not bill the client for that extra time.

Quoting a range of hours not only allows you to invoice the client for less than the maximum if you don’t need all the hours (never a problem), it also gives you a bit of a safety net in case some sections of the text need extra attention. However, some editors quote and charge by the word, which has two advantages: both parties know beforehand what the costs will be, and as an editor you don’t have to keep track of the time spent on the text. A huge advantage if you are easily distracted by incoming emails (just close the program – works wonders!) or need to stop regularly while editing to answer the phone, feed the kids, hang up the washing, take the dog out, etc. Although you will need less time to prepare your quote, don’t forget to have a good look at the text before you start! This is of course also the case if you charge per hour. After all, some texts have multiple authors and you want to avoid nasty surprises.

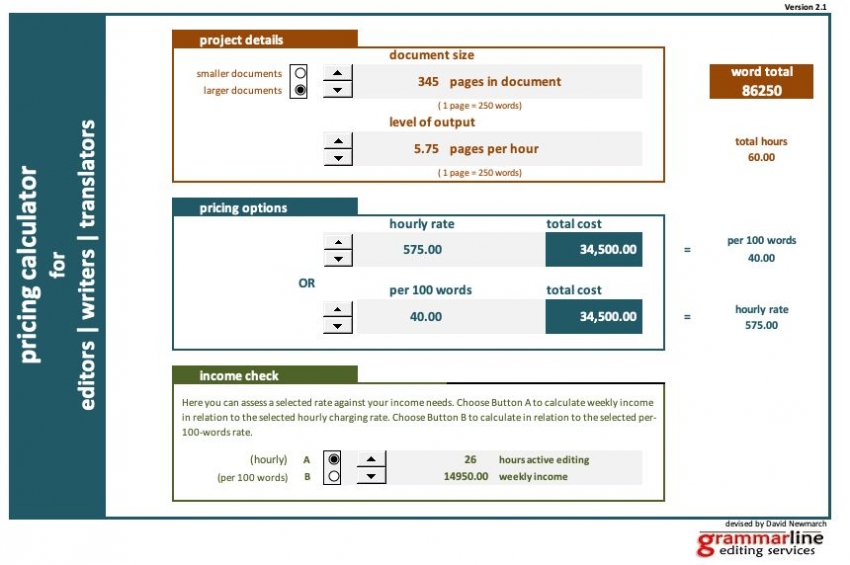

Handy pricing calculator

You can of course use both hourly rates and word rates depending on what each client prefers. A post in April 2016 on the Facebook page of the Board of Editors in the Life Sciences’ points to a handy pricing calculator (pictured above) that allows you to see the equivalent fee per hour, per page, or per 100 words according to manuscript length and the editing level required according to ‘pages-per-hour’. Not only useful for editors but also for translators and writers. The Excel calculator is available for free via the website of the US-based Copyediting-L email discussion list and generously provided by David Newmarch.

It is a little cumbersome in that it is based on a page count, but if you have a word count then dividing by 250 will give you the page count to fill in. And you cannot actually type numbers in the spreadsheet so it takes a bit longer to fill in your rate and your speed. But... once you do, you can compare per word and per hour pricing options and also calculate what your weekly earnings are based on your rate and number of billable hours. And as I mentioned in part 1 of this series, paying attention to rates and earnings is an essential part of running your business.

I have not mentioned specific rates. What you charge will likely depend on your experience and should be a combination of what you feel you are worth and what your clients are prepared to pay. If you find it hard to know what to charge then just ask around – in my experience other SENSE members are happy to tell you what they charge, just not online. And that is one of the many reasons for attending SENSE workshops and SIG meetings and chatting with fellow language professionals. The results of SENSE’s 2012 rates survey indicate that rates for editing vary from €30 to €80 per hour, the average being around €55 (use the pricing calculator above to convert this to a word price).

[1] Nigel Harwood, Liz Austin & Rowena Macaulay (2012) Cleaner, helper, teacher? The role of proofreaders of student writing, Studies in Higher Education, 37:5, 569-584 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.531462

Those of you who proofread for students should not miss the upcoming UniSIG meeting, on Friday 8 October! Nigel Harwood, Professor of Applied Linguistics at the University of Sheffield, UK will be speaking on 'The ethics of "proofreading" student writing at UK universities'. His research interests include academic writing, English for specific and academic purposes, and TESOL materials/textbook design. He has recently published a series of articles on the proofreading of student academic writing. Registration for this event closes at 9:00h on 8 October.

|

Blog post by: Sally Hill LinkedIn: sally-hill-nl Twitter: SciTexts |

Sizzling Summer Series recap: Terminology Extraction and Management

Written by Jackie Senior

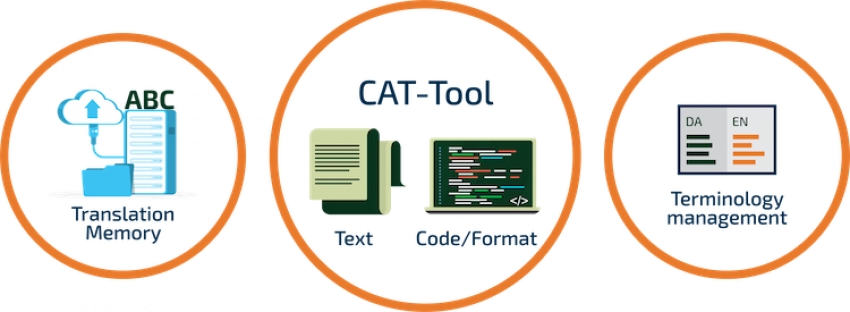

On 29 July 2021, I joined a group of fellow editors and translators to follow this SENSE workshop given by experienced CAT tool trainer Angelika Zerfass, who joined us online from her office in Germany.

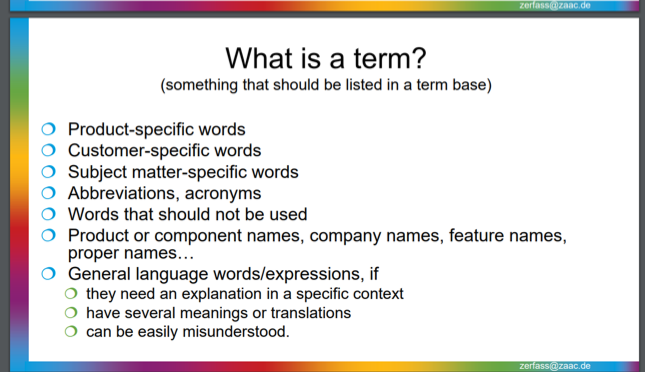

Her workshop started with an introduction to terminology management before moving on quickly to some very practical points: the amount of time you need (or want) to spend on this aspect of your work, how to tackle extracting terms from text, how to structure your data, the useful metadata to include, advanced tips for using Excel, and much more.

During her introduction, Angelika first stated the old adage ‘terminology is WORK’ – which is true whether you’re a multilingual or bilingual translator, or a monolingual editor. Her second essential point was that a system or database only becomes truly useful once it reaches a certain size. The tipping point of the number of hours put into building up your database versus when it becomes really useful to you will be different for everyone, but it’s certainly something to be aware of if you don’t have any system in place yet. Nevertheless, having some means of standardizing your output (per client/per topic/per document or publication) is strongly recommended for all text workers.

She then went on to tell us that the way in which you tackle your terminology management can depend on whether you adopt the viewpoint of a terminologist or of a user. For most SENSE members, practical issues will determine what you want from a terminology tool and how you can best structure it. This means starting by defining what you want to use your term database for. For example, for translators, terms cannot always be managed on a one-to-one basis, so it’s necessary to include fields for examples of their use and explanatory phrases.

Angelika went through some of the software tools that can be used for extracting terms (see list below). Some are free. She noted that the metadata you include with a term can prove essential in helping you decide on whether to use it in a certain setting. Metadata can include fields for source, reliability, dates for entry or added comments, examples of use, whether it’s required by a particular client, and for marking ‘forbidden’ terms or false friends.

Finally, Angelika summarized her points and noted that term lists and term databases are both useful and important for maintaining the quality of your work. And they will become even more important for improving or checking machine translation output!

Personally I found it interesting to see how these tools are developing, how well they interact with MS Word, and what one can use them for (having started my career with piles of dictionaries and a notebook next to my paper texts). For any language professional I think it’s essential you have some way of ensuring consistency between your texts and for individual clients. If you aim to work another five years or more, it’s certainly worth investing the effort to compile your own databases.

Terminology Extraction ToolsConcordance tools Term extraction tools / components of translation memory tools

Web-based term extraction

Check also: |

SENSE Summer Social: The wordsmith challenge!

Written by Naomi Gilchrist

On Friday 27 August 2021, a group of SENSE members got together in a Zoom session to have some fun and compete in a virtual wordsmith competition. The session was facilitated by SIG & Social Events Coordinator Maaike Leenders and hosted by Jacqueline from the 100-point challenge.

The Riddle

There were 16 participants who were divided over four teams. After the introduction and a quick briefing on how to play ‘The Riddle’, the teams were sent into their own breakout rooms.

For the next 45 minutes, we looked at ten unique problems, which would provide clues that we would need to solve one Master Riddle. It was a race against time and that time went by quickly…

The ten problems consisted of a mix of visual puzzles, riddles and logical reasoning. A little bit of everything really, all very engaging. Fortunately, the teams were also allowed to call in the help of our good friend Google.

The puzzles were not too difficult, but they weren’t extremely easy either. Our team was able to answer the questions within the allotted time – some of the other teams even finished with time to spare. They got to try their hand at tackling a few movie-related bonus questions.

The team that submitted their answers first and managed to solve the Master Riddle won the challenge. (There was no prize, it was just for fun.)

We all agreed that it was a very enjoyable session and a fun way to connect with other SENSE members. A lot of us language professionals usually work alone, so this was a good opportunity to engage in some teamwork.

Catching up

After the challenge was over, we joined a separate Zoom session and spent some time catching up while enjoying drinks and snacks.

I personally thought that it was a great way to spend a Friday afternoon: getting to know other SENSE members, testing our wits together and informally saying goodbye to the summer holiday months. My sincere thanks go out to the event organizers!

In part one of her 2016 series of business how-to’s for eSense, Sally Hill tackled the question of pricing strategies for translation, websites and otherwise.

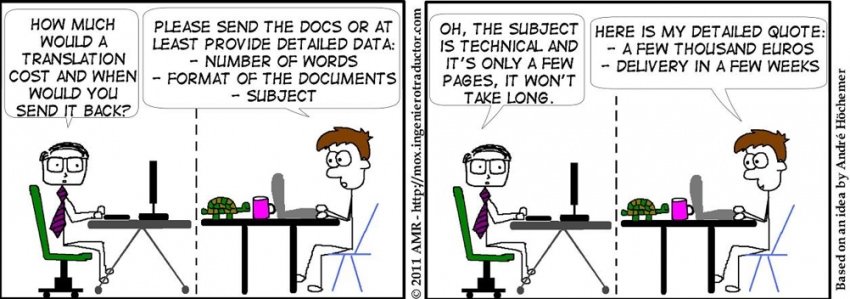

A request comes in by email asking if you can do a job and you reply with a price and a deadline. If you’re a freelancer then this is something you probably do on a weekly basis. If the request is from an agency, there may be little room for negotiation in terms of pricing and deadline. But whoever you are dealing with, you still need to check the details of a job carefully to make sure the terms do not deviate from what you normally do or from what you have previously agreed with that particular client. Here, I talk about some of my own experiences when quoting for jobs as well as providing tips for other freelancers and links to further reading, both online and in print.

Examples from SENSE members

The difficulties that can arise when putting together a quote for a client are apparent from several questions posed on the SENSE forum. So let’s consider a couple of examples, starting with a question I myself asked about quoting for a transcreation job. A regular client had sent me 11 slogans to translate from Dutch to English, some with plays on words, assuming I would charge my regular per-word rate. Although I could have passed on this juicy job (creative juices juicy, not loadsamoney juicy) to someone more familiar with translating marketing texts, I knew the terminology from translating the client’s website and wanted to have a crack at it myself. But because I knew this could easily take me the best part of a morning, depending how much of a perfectionist I wanted to be, I wondered how many hours I could reasonably quote for it – especially since the client was assuming it was no more than about half an hour’s work.

I got some very useful advice from colleagues, both on the Forum and by phone, which basically came down to “charge by the hour and quote a range”. In the end, I quoted for 2-4 hours and charged the client for 2. Of course, this did not include the time spent deciding on how much to quote – I put this down to a learning experience/CPD useful for future jobs.

What did I learn from this? That it’s essential to find out what the client will use the transcreated texts for (internal memos only or global billboards?) as well as whether all the text will be used (my client selected only the five they liked most to print onto magnets for internal use). But also that you can sometimes overthink things and easily end up spending far more time quoting for a project than just getting on with it. For a client who offers me interesting well-paid projects, who I want to keep happy and impress with good service, I would now even consider doing such a job for free, or perhaps add on a little extra to my next invoice. So what you quote may also depend on your relationship with the client.

When quoting for a website translation, one SENSE colleague ran into the problem of doing an accurate word count. The client had suggested they give him access to the site via their portal in order to directly enter the translation online. But, of course, to come up with a quote he needed an idea of how long the project was going to take him, so a rough word count was needed. Entering the translation directly would also mean having none of the benefits of a translation tool or word processor – perhaps not even a spell checker!

Some colleagues suggested that an export into Word was the only way – to be done either by the client or the translator himself (and charged for accordingly of course). But it seems there are tools out there to at least help with the word count side of things. TransAbacus was mentioned as a possible website word counter. According to the TransAbacus website, this software “gets a website address or URL and returns the list of pages on the site, with the number of words for each one.” Sounds ideal, and at USD 34.95 for the full version, it’s not too pricy. A trial version is free and has the same functionality as the full version, but only displays the first 5 pages/files for the website being counted. If you have purchased and tested out TransAbacus, I’m sure other members would love to hear about your experiences with it on the Forum under the computer-related category.

This thread also side-tracked into counting words in PowerPoint files: apparently CAT tools can but other counting tools cannot. And do note that if you include in your quote a hefty fee for converting files to Word (from PDF or copy-pasting from a website) the client may miraculously find that they can do that themselves or find the relevant Word file.

If you’re a SENSE member, make sure to visit the Forum to read these other threads related to quoting:

- On counting words in a website for an editing quote

- The disadvantages of quoting a per-page rate

- A question on per-word rates for editing, plus some useful tips on calculating an average number of words per hour

Pricing problems

Apart from deciding how long something is likely to take you (in terms of text length or number of hours), you need to know how much to charge, whether this is per word, per hour or per project. Much has been written on deciding on a pricing strategy to match your target income. For translators I highly recommend from my own bookshelf both Chris Durban’s The Prosperous Translator, which has a chapter on pricing and value (Chris also spoke for SENSE in 2012), and Corinne Mckay’s How to Succeed as a Freelance Translator, which has some great tips about setting your rates and payment terms.

How do we get around the issue of a complicated or poorly written source text taking you longer to translate or edit than a straightforward or well-written text? No problem if you charge by the hour of course, but since most translators charge per word you need price zones – different rates for different texts.

On her blog Corinne Mckay suggests a green zone rate at which you would almost never turn down work, as long as the project is within your capabilities. The yellow zone is a rate that’s not ideal, but worth taking a look at – one you consider when work has been a little slow or if a project is particularly interesting, or when there’s some non-financial reason to consider it. Finally, the red zone is work that you turn down because it’s just too low-paying. To have a viable business, she says, you have to have a red zone.

This also ties in with what English-Swedish freelance translator Tess Whitty says in a podcast on her website Marketing Tips for Translators. In her podcast Tips on pricing strategies, negotiation and raising prices for Translators, Tess tells us that the better you are at negotiating your price, the better your rates will be. I agree – and I speak from experience – that giving your rates serious thought and making them part of how you market yourself as a business will put you in the right mindset for getting paid what you are worth. Such a mindset will give you confidence in negotiations with clients and hopefully help you to raise your rates as you gain more experience and become more specialized as a translator.

A pricing strategy for translation work that I am starting to hear more about is quoting on a per project basis. This is ideal for direct clients who don’t need – and are not interested in – a detailed breakdown but just want to know how much, period.

Another member told me about an Excel spreadsheet that she uses to calculate a total price for a new job. She copies the word counts from Practicount and from her CAT tool into the spreadsheet, then adds her per-word price and applies any discounts she thinks this client deserves (e.g. for similar files or for matches with previous translations) and the spreadsheet calculates the total price to the nearest 10 euros.

A final note relating to volunteering: if you like the sound of any of the books mentioned above, I highly recommend volunteering for our Society – those thankyou book tokens can come in handy!

This article first appeared in eSense 41 (2016). Cartoon reproduced with permission from Alejandro Moreno-Ramos, a freelance English & French to Spanish translator. ‘Mox is a young but well-educated translator. Two PhDs, six languages … and he hardly earns the minimum wage.’ The cartoons also feature his sidekick Mina (a turtle), Pam the evil project manager and various other characters. Please see Mox’s blog for more cartoons and to order his books.

|

Blog post by: Sally Hill LinkedIn: sally-hill-nl Twitter: SciTexts |

Sizzling Summer Series recap: applying Plain Language for accessible, user-friendly texts

Written by Daphne Visser-Lees

A small but enthusiastic group of language professionals gathered by Zoom to participate in this SENSE summer workshop. Speaking to us from South Africa, John opened with a quote from George Orwell: ‘The message is important, not the fancy language wrapped around it.’ And this set the tone for the workshop.

The group quickly established that we were all faced with similar problems. Even in this day and age, many writers continue to think that the more complex their writing is the better it is. Unfortunately in the process they often lose their natural (aka plain) voice completely. It is up to editors to render the authors’ messages readily understood at first reading by dispensing with obscurity, inflated vocabulary and convoluted sentence constructions.

Over the course of three interactive 50-minute sessions John led us through the application of Plain Language principles to real-life examples of poorly written English. We looked at adopting a reader focus, sentence length and complexity, noun strings, jargon, the use of the active and passive voice, and much, much more. John’s practical plain English approach included tips on ideal sentence and paragraph length, where and how to shorten sentences (a particularly useful section), and the value of vertical lists.

Whatever stage you are at in your editing career, I can thoroughly recommend taking part in this workshop. It not only provides concrete and useful tips for tackling text that at first sight seems impenetrable, but also gently encourages you to take an objective look at your own editing style. Although I like to think I keep up to date with modern English usage, I was somewhat surprised to realize how many archaic words I continue to use, but I am happy to adopt the suggested plain English alternatives.

Following the workshop, John sent us his PowerPoint presentation. Every single slide contains one or more useful nuggets of plain language advice. I will be keeping it easily accessible on my desktop to consult on those days when second language interference threatens to take the upper hand, or when dealing with a client who insists on using unnecessarily complex language. After all, as John reminded us, part of our job as editors is to educate the client by emphasizing that plain language gets the message across more effectively.

For more CPD opportunities, check out the SENSE Professional Development Days, on 18 and 25 September. This year's programme is all about horizontal knowledge-sharing and learning from your peers throughout your career. Topics include digital nomadism, the linguistics of wine, branding to money management, balancing multiple niches, collaborative translation, intercultural communication, the SENSE mentoring programme, and battling imposter’s syndrome. Tickets are €25 for members (non-members pay €40) and grant access to both days. Not a SENSE member? Click here to read about the benefits of joining the Society!