By Jan Klerkx, 22 January 2026

On 28 November 2025, SENSE member David Barick, experienced teacher, editor and translator of academic research texts, presented a lively interactive Zoom talk under the catchy title of ‘Do they still need me?’ on the fraught question of whether AI will replace humans as teachers, editors and translators of academic research writing.

David started by referring to some workshops on the topic that he had recently attended. A European Association of Science Editors (EASE) panel discussion concluded that ‘ChatGPT has a weak ability to differentiate between good/excellent and weak/OK research.’ At the same panel discussion, James Zhou presented results of a survey among researchers from 110 institutions, asking whether they found LLM tools helpful for their academic writing. Nearly 60% of respondents found them ‘helpful’ or ‘highly helpful’, and about 20% found them ‘much more helpful than most human feedback’.

David then went on to discuss some of his own experiences of what LLMs, specifically ChatGPT, can do when it comes to editing scientific papers. He had asked ChatGPT to do some of the editing exercises he uses in his own teaching. He commented on paragraph structure and paid specific attention to coherence techniques, including given-new patterns, repetition of key words, grammatical parallelism and the use of transitional phrases and cohesive markers. He asked the audience to comment on the examples too, using the Zoom chat function.

In an example on thermonuclear energy production, ChatGPT did indeed improve many of the coherence problems, but it also produced longer sentences than in the original, even though it generally recommended shorter sentences.

When asked to comment on the use of coherence techniques in a sample text on endometriosis, ChatGPT correctly identified the use of repetition of key terms and the use of linking devices and parallel structures. The program’s editorial judgement was that ‘minor changes would likely be enough to make the text publishable for a specialist readership’, but that ‘more intervention would be beneficial’ for a more general audience. However, the suggestions it made for such interventions were minimal and not very helpful. Under the heading ‘Break up long, dense sentences’ it produced a suggestion that actually resulted in a less concise paragraph! It also suggested breaking up a nine-sentence paragraph using subsections with separate headings, which journal editors would probably not appreciate.

The final example concerned a longer text (an entire introduction section) on alcohol consumption patterns, which was judged by the audience to be poorly written. They suggested it had not been written by a native speaker of English. ChatGPT also recognized this and even correctly surmised that the text was written by an author from Spain or France (the author was in fact Spanish). It also correctly identified many of the problems of coherence, grammar and collocations. Other suggestions, however, were less helpful and often involved introducing words or phrases that did not add useful content and actually hampered the flow. Some of the additions sounded very generic, not specifically relating to the topic of the text, e.g. ‘This review aims to synthesize recent findings, identify consistent patterns of impairment, and highlight methodological limitations to guide future research.’

Some of ChatGPT’s comments showed that it failed to distinguish between closely related words, e.g. ‘binge drinking’ and ‘hangover’, which it both referred to as patterns of alcohol intake.

Finally, David showed us what ChatGPT had to say when it was asked: ‘ChatGPT can give extensive information on how to write a scientific research article. Do you think that it is a satisfactory substitute for human teachers of this subject, or that it will become so in the future?’ ChatGPT’s answer was rather diplomatic: it claimed that ChatGPT (or AI in general) was already good at explaining structure and conventions clearly, providing quick feedback and editing assistance, generating tailored practice tasks and summarising or explaining complex research writing guides. In contrast, it suggested that human instructors would still be better at mentorship and judgment, understanding nuance and emotion, evaluating scientific reasoning and teaching through dialogue and modelling.

David’s final conclusion was therefore that AI would not replace writing instructors any time soon, as humans will still be better at critical thinking and social learning. AI may function as a complement to human teaching, but a good teacher will always add useful extras to what AI can do.

|

Blog post by: Jan Klerkx |

By Tracy Brown, 5 January 2026

‘I write to know what I think.’ (Flannery O’Connor)

O’Connor’s insight captures a truth at the heart of writing: the act itself is a journey of discovery. Each sentence we wrestle with, each paragraph we revise, brings clarity, not just to our readers, but to ourselves. Writing is thinking made tangible. But what happens when artificial intelligence enters the picture? Can AI become a partner in this process, or does it risk short-circuiting the very mechanism through which writers discover their own thoughts?

AI has undeniable appeal. For experienced writers, it can generate ideas, suggest phrasing and help navigate the occasional bout of writer’s block. But for new writers, particularly those who have never written without it, AI can be more of a crutch than a catalyst. The difference lies in the relationship between thinking and writing, which is a relationship AI, however sophisticated, cannot replicate.

The value of writing without AI

At its core, writing is a process of self-clarification. When we write unaided, we confront our ideas in their raw, unfinished form. Struggling to articulate a thought forces reflection: we wrestle with ambiguity, untangle contradictions and confront gaps in understanding. This struggle is where voice is born. Style emerges not from polish, but from persistence, from returning to the page again and again until the words sound like us.

Consider a beginner drafting an essay or story. They pause, scratch out sentences, reconsider word choice and sometimes abandon an idea entirely. This friction, the mental resistance encountered when shaping thought into language, is essential. It is not just about grammar or flow; it is about discovering what we think and how we feel. Writing teaches us our own minds.

When AI steps in too early, it smooths over this friction. It offers fluency without struggle. And while that can feel productive, it can also bypass the very work that makes writing meaningful.

How AI can help writers

This is not an argument against AI. Used consciously, AI can be a genuinely useful tool, especially for experienced writers who already have a sense of voice, perspective and purpose. In those cases, AI functions less as a replacement for thinking and more as a support for execution.

Some of the ways AI can help include:

- Outlining and structuring ideas

AI can help organize complex material, suggest logical flows or surface gaps in an argument. This is particularly helpful when a writer already knows what they want to say but needs help shaping it. - Editing and revision

AI can identify awkward phrasing, repetition or unclear sentences. Crucially, this only works if the writer approaches its suggestions critically. Without that critical stance, AI becomes a mirror that simply validates whatever is already on the page. - Organizing scattered thoughts

For drafts that exist as notes, fragments or rough paragraphs, AI can help cluster related ideas and propose a clearer structure. - Ensuring consistency of voice and tone

For longer projects, AI can flag inconsistencies in tone or terminology, helping writers maintain coherence across chapters or sections.

In all these cases, AI works best as a secondary tool. The thinking still originates with the writer. The judgment still belongs to the writer. The writer remains in control.

What AI cannot do

What AI cannot do is give you insight into yourself.

It cannot tell you what you actually believe, or why a particular idea matters to you. It cannot help you arrive at a position you did not already hold. It cannot replicate the internal shift that happens when, halfway through a paragraph, you realize you were wrong or that the real point is something else entirely.

Finding your own voice is not just about sounding distinctive. It is about discovering your own ideas, your own opinions, your own way of seeing the world. That discovery happens through effort. Through uncertainty. Through writing sentences that don’t quite work and staying with them anyway.

AI also cannot give you the thrill of a breakthrough, the moment when something clicks, when a vague feeling crystallizes into a clear thought. Those moments are not incidental to writing; they are the reward. And they are intrinsic.

Intrinsic vs. extrinsic rewards

This is where the deeper risk lies, especially for new writers.

Writing offers intrinsic rewards: discovery, clarity, the quiet satisfaction of understanding something more deeply than you did before. These rewards emerge slowly, through effort.

AI, by contrast, offers extrinsic rewards: speed, completion, polish. A finished paragraph. A clean draft. The sense of being ‘done’.

When writers rely too heavily on AI, the balance shifts. Completion replaces discovery. Output replaces insight. The work may look finished, but the writer has learnt less from it.

For beginners, this matters enormously. If you skip the struggle, you skip the growth. You may produce text, but you do not develop the muscle of thinking through writing. Over time, that loss compounds.

Tool or crutch?

For experienced writers, AI can be a powerful tool ‒ one that accelerates, supports, and occasionally challenges their thinking. For new writers, especially those who have never written without it, AI risks becoming a crutch that dulls curiosity and replaces the hard but necessary work of self-discovery.

The distinction is not about technology. It is about intention.

If writing is merely a means to an end, AI may be enough. But if writing is how you come to know what you think, how you find your voice, refine your ideas, and understand your own position in the world ‒ then no machine can do that work for you.

In the end, the writer still has to write.

|

Blog post by: Tracy Brown |

By Claire Bacon, 17 December 2025

It’s that time of year again – time to renew my SENSE membership. I have now been a member for 10 years, so what better time to look back on how SENSE has supported me in my work over the years?

The people

For me, one of the biggest advantages of SENSE is the camaraderie within the Society. I have always felt very welcome in SENSE, even though I live in Germany and do not speak Dutch. When I joined SENSE back in 2015, I was in the early stages of leaving academia to set up my language editing business. Everything was new and a little overwhelming, but my fellow SENSE members, many of whom had been in the business for years, helped me enormously with their advice and encouragement. As time passed, networking within the Society helped me to build up my client base and a thriving editing business. It also introduced me to exciting new work opportunities, including teaching scientific writing, which I enjoy tremendously. When harder times hit us a few years ago, it was extremely helpful to be able to discuss these challenges openly with fellow members at in-person and online events.

Getting involved

A great way to network is to get involved! At my first SENSE event (the 25-year Jubilee in 2015) I agreed to write an article about the event for the SENSE magazine. Shortly after, I joined the SENSE Content Team, which is responsible for producing and editing the content that SENSE publishes. Writing and editing articles for the SENSE magazine and later the SENSE Blog not only helped the Society but also increased my visibility among fellow language professionals. This has led to many referrals of work over the years. You can find out more about volunteering for the Society here.

Professional development

SENSE also offers a variety of opportunities for professional development, and there really is something for everyone! Over the years I have attended a number of professional development days, conferences, and workshops organized by the Society – both online and in person – and have always been impressed by how much these events cater to my needs as a language editor for academics in the health and life sciences. As well as learning what’s new in the industry and sharpening my skills, these events were a valuable opportunity to meet old friends, make new contacts and exchange useful ideas. There is always something going on in SENSE and you can find out more about upcoming events here.

Special interest groups

SENSE caters to the specific needs of its members through special interest groups (SIGs). Like many editors, I sort of stumbled into the profession by accident! An advantage of this is that I became a very niche editor, using my background in scientific research to shape the kind of editing work I do – mainly scientific research articles and grant proposals. Fortunately for me, SENSE has two great SIGs that offer meetings for editors working with academics: SenseMed and UniSIG. These meetings have been a great way to support my specialized editing work over the years. You can find out more about the many SIGs that SENSE has to offer here.

Join the community!

I doubt I would have gotten as far as I have as a language professional if I hadn’t joined SENSE. The Society welcomes all language professionals and offers a vibrant and supportive community. To learn more about the many benefits of joining the Society and what it can offer you, visit the SENSE website.

|

Blog post by: Claire Bacon |

By Santiago Gisler, 27 November 2025

How should writers use generative AI? Not at all, if possible.

The cabaret-like entry of ChatGPT into the public stage left us in awe. We were suddenly confronted with a technology accompanied by waves of contradictory promises. On the one hand, we were told that AI would transform society, improve medicines, or help us create better content. On the other hand, many warned it would replace professionals, introduce harder-to-control misinformation and plagiarize content.

Whether we should use generative AI for writing is a nuanced question. I remain skeptical, but the more I use and learn about it, the more I’m inclined to recommend that content creators avoid AI whenever possible.

My skepticism derives from the numerous problems associated with the technology. I won’t even delve into its broader ethical issues, such as environmental impact, human rights abuses or its use in developing armaments. Because even if we focus solely on our work as writers, the problems of excessive AI use still outweigh its benefits.

As writers, we have valid concerns: Will AI content creation and usage replace human work? How can we use it responsibly and accurately? These are critical and valid questions. Still, since I haven’t fully embraced a purist approach, I won’t advocate abandoning AI altogether. Instead, I’ll share my current perspective on generative AI and how to approach it cautiously in writing.

AI is really just a large language model

Given the almost anthropomorphic qualities people tend to attribute to generative AI – even in academic circles – it’s worth clarifying these tools’ alleged intelligence. Their human-like characteristics have created immense marketing potential, portraying them as intelligent, emotional or objective.

At a recent philosophy workshop on AI ethics, the event organizers repeatedly attributed god-like properties to ChatGPT, including future motives and feelings. Some attendees had personalized their ChatGPT to behave like famous characters, such as Harry Potter. This excessive decoration highlights the over-the-top marketing behind generative AI tools and reminds us to treat them with caution.

In reality, generative AI tools like ChatGPT are large language models (LLMs), sophisticated mathematical models built on powerful Transformer architecture that recognize patterns in language. They don’t think; instead, they predict the next likely token (a piece of a word or a whole word) based on patterns they have learnt from their training data, context and probability. This process continues until the model meets a predefined stop condition, resulting in a coherent, human-like response.

Although impressive, these outputs lack intelligence in the sense of logic, reflection or problem-solving. LLMs merely repeat data they’ve been trained on – data from other writers – and provide a statistically probable outcome. With this in mind, we begin to see where an over-reliance on LLMs becomes problematic in writing.

AI weakens our writing and thinking

Loosing the chance to develop

I have a love-hate relationship with my old articles. All their grammatical mistakes, clumsy formulation and misused expressions make me cringe. Still, embarrassing as they are, those hair-raising mistakes also highlight my writing progress and stylistic improvements over time.

As we increasingly rely on generative AI tools for writing, we lose these auto-reflective feedback processes, and with that, the opportunity to develop from them. This AI trap specifically affects new writers who haven’t had the chance to develop a personal writing style.

AI-related hallucinations are also a big problem for new writers or anyone new to a topic. LLMs are prone to make things up – a lot. They deviate from facts, contradict themselves or the prompts, or include nonsensical information. These hallucinations result from issues with the quality of the training data, generation methods or input quality, and are challenging to identify unless the writer is somewhat familiar with the topic.

A feedback loop of mediocre and erroneous content

Other critical drawbacks of generative AI models relate to our future information landscape and our ability to think critically and solve problems. Writing and everything around it requires an ability to think critically while organizing and structuring our perspectives to make an impact.

Excessive AI use strips away these critical aspects of impactful writing and traps the text, language and opinions within a generic, all-pleasing framework.

The more we rely on AI-generated content, the greater the likelihood that future AI model training will depend on dull and sometimes flawed data. It becomes a positive feedback loop of generic, impersonal and blunt content that is just… there.

Generative AI bots accounted for more than half of all web traffic in 2024, a figure that is expected to increase each year. LLMs may initially help us create coherent and seemingly credible content. However, as the information landscape becomes increasingly reliant on AI-generated content, it draws audiences away from our human-made, personal and engaging content, ultimately reducing our online visibility and readership.

What we’re left with are accumulations of LLMs trained on LLM content, with fewer personal experiences and more hallucinations.

How to use generative AI

So, how do we turn all this skepticism and negativity into a constructive approach? My answer would be that, if we necessarily need to use generative AI models for our writing, we’re better off using them sparingly and intentionally.

I’d recommend approaching it in the following way:

- Understand the topic by researching literature and videos. Although selective and sometimes unreliable, applications like Copilot can help you with your first references if you’re unfamiliar with the topic.

- Use your own words when drafting, and highlight any statements, expressions, phrases or sentences you’re unsure of.

- Ask AI models targeted and specific questions about your highlighted sections. Instead of asking ‘Does AI hallucinate?’ ask, ‘What are the most common factual errors or hallucinations that occur when writing about quantum computing?’

- Use multi-shot prompting, in which you submit several prompts with comprehensive context and examples before submitting your specific request.

- Specify your prompts: ‘Proofread this text for grammatical errors and factual inaccuracies only. Do not change the style or phrasing unless it is incorrect. Flag any sections that seem to lack supporting evidence.’ Asking AI tools to ‘improve the text’ will always prompt them to suggest excessive changes, regardless of how well you write.

- Explicitly highlight all possible answers when asking a closed-ended question. Instead of asking, ‘Does this summary miss any key points?’ ask, ‘Does this summary miss any key points, or is it complete and accurate?’ This reduces the risk of the tool conforming to what it thinks you want.

- Use neutral language and avoid suggestive phrasing such as ‘Isn’t this a great sentence?’

- Approach all the information you receive from AI models with sound skepticism.

Eventually, we may realize that all these processes cost more time than simply researching and writing on our own. I’m not here to discourage anyone from using AI tools. But perhaps a relevant question is whether we really need AI at all from a linguistic, professional and ethical perspective.

|

Blog post by: Santiago Gisler |

By Jackie Senior, 13 November 2025

Given the recent developments in AI, I carried out a survey to discover how SENSE members view generative AI tools, the changes in their language work, and their future. The survey was carried out online in February-March 2025.

1. Survey results

Demographics

- There were 79 anonymous responses (33% of SENSE members), with expertise spread across the SENSE spectrum (editing, translation, teaching, copywriting, transcreation, etc.).

- 86% of respondents have been language professionals for more than 10 years.

- The data confirmed that SENSE is an ageing society, with 53% of respondents older than 60 years and 42% between 40 and 60 years (as compared to 30% and 59% in a SENSE survey in 2014). In the free text responses (49/79), 15% of respondents said they were already receiving a pension or would be soon.

Generative AI: use and perceptions

- Most respondents (86%) already use older tools like DeepL, Google Translate, SDL Trados, MemoQ or PerfectIt, either frequently or some of the time.

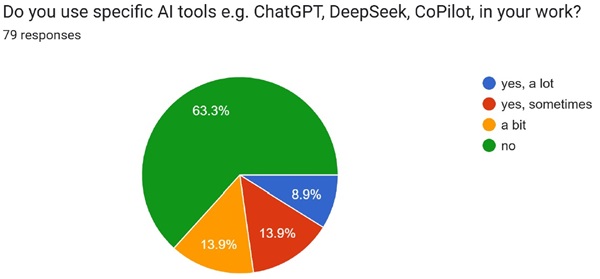

- The majority of respondents (63%) reported not using generative AI tools in their work, although 9% reported using them ‘a lot’.

- Respondents more often reported negative feelings about what AI would bring to their profession (41% apprehensive; 17% pessimistic), with only 16% being optimistic/fairly positive.

- Only 17% reported having been asked to use generative AI tools by a client, publisher or agency. I did not enquire whether they had actually used generative AI for that particular job.

- How responders feel about generative AI was quite evenly split: 11% were excited, 27% interested, 21% neutral, 28% apprehensive and 13% not interested.

- 74% reported using these tools for personal tasks at least sometimes.

The changing ‘work-scape'

- 66% of respondents had had increased their range of language-based work in the last 5 years, and 77% had added a completely different kind of service.

- 30% have other interests/skills they could develop (into a service or money-earner), or a plan B, while another 42% reported they may have other options.

- 40% were the sole earner in their household, 38% a shared earner, and 23% a minor earner. 54% had other sources of income outside their language services (e.g. pension).

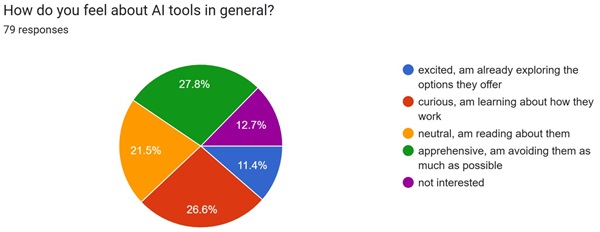

- Slightly more than half (52%) have seen a drop in income from their language work in the past two years.

Statistical analysis

- There seems to be a relatively small group who have a positive attitude to AI and use it both at work and for personal tasks, and a larger group who are neutral or negative and not using AI at all.

- No significant correlation was found between the use of or attitude toward generative AI and the respondents’ age group, but there were very few younger (under 40 years old) respondents.

- Use of AI and feelings about it at work were largely unrelated to the kind of language work being done.

2. Implications for SENSE

- SENSE was an ageing society in 2015, and is now 10 years older, with the number of members dropping fast.

- So what do the working members want to see in their professional society?

- How relevant can SENSE be for its members in these changing times?

- How does the Society need to change – or should it just retire quietly?

- SENSE must determine its members’ age groups. (At the moment this information is no longer collected because of the new privacy law. Each member must give permission for their age to be processed in Society information.)

3. What can we do?

- Keep in mind this is not the first time the field has faced a major change in our mode of working.

- Build personal relationships with clients, keeping the human face in your work. This can be challenging for freelancers, but it is clearly something that differentiates us from machines.

- Take courses and follow resources that improve our awareness of how to use generative AI tools, and develop hands-on experience that helps us understand what they can and can’t offer.

- Be able to show clients you can work with these tools, but also that you offer skills AI tools do not have.

- Adopt better pricing strategies that reflect the changes in the field, e.g. fee per hour, valuing your time, adding administration charges, and raising rates each year.

- Build reciprocal relationships with other professional colleagues that improve both the quality and continuity of your services: someone to watch your back, share skills and take up the work that you can’t.

- Look to expand the services you offer, whether in language services (e.g. offering workshops) or in new directions.

Credits go to Kate Mc Intyre, who compiled this blog post, and to Clare Wilkinson, who did the statistical analysis of the survey results. The PowerPoint PDF from Jackie Senior’s presentation to the SENSE 35-year Jubilee Conference on 20 June 2025 is available to SENSE members in our Library. Please send any comments to Jackie (email address is in the membership directory on the SENSE website).

List of resources

- The SENSE Blog

https://www.sense-online.nl/sense-publications/blog - ‘AI in Medical Writing and Editing’ training course

Emma Nichols

https://www.aimwecourse.com/ - AI Tools Boot Camp

Avi Staiman

https://www.aclang.com/ai-bootcamp.php - Generative AI in learning, teaching and assessment

Open University (UK)

https://about.open.ac.uk/policies-and-reports/policies-and-statements/generative-ai-learning-teaching-and-assessment-ou - BBC news and reports on AI

https://www.bbc.com/innovation/artificial-intelligence - Business coaching, workshops, a blog, newsletter

Lion Translation Academy (Joachim Lépine & Ann Marie Boulanger)

https://www.liontranslationacademy.com/ - Leaving academia: becoming a freelance editor

Paulina S. Cossette

https://AcadiaEditing.com/BecomeAnEditor - How to build a global academic editing business

(podcast interview by Paulina Cossette with Marieke Krijnen)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jNfzf1wkvyk - Editing synthetic text from GenAI: two exploratory case studies

Michael Farrell (2024)

http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.16045.81128 - Survey on the use of GenAI by professional translators

Michael Farrell (in ‘Translating and the Computer 46’, 2024, pp 23‒34;

©AsLing, the International Society for Advancement in Language Technology

https://www.tradulex.com/varia/TC46-luxembourg2024.pdf#page=23 - Henley Business School poll of 4500 people (2025)

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c3rpx1rl2nlo - https://societyofauthors.org/2024/04/11/soa-survey-reveals-a-third-of-translators-and-quarter-of-illustrators-losing-work-to-ai/

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/sep/07/if-journalism-is-going-up-in-smoke-i-might-as-well-get-high-off-the-fumes-confessions-of-a-chatbot-helper

- https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/nov/04/dutch-publisher-to-use-ai-to-translate-books-into-english-veen-bosch-keuning-artificial-intelligence

- https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/apr/16/survey-finds-generative-ai-proving-major-threat-to-the-work-of-translators

- The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading’s (CIEP, UK) knowledge hub has a few items on AI

https://www.ciep.uk/knowledge-hub/search-the-knowledge-hub.html?searchQuery=AI

|

Blog post by: Jackie Senior |

By Maria Sherwood Smith, 30 October 2025

On 26 September 2025, UniSIG came together online for a presentation by Joy Burrough-Boenisch on ‘Dealing with maps in scientific and scholarly texts’. The talk was based on the presentation Joy gave last year at METM24 in Carcassonne, and she had updated it to include some recent cartographic debates.

Joy started by going back to the basics, introducing us, via an article by geographer Caitlin Dempsey, to eight elements that make up a map. The most important ones for the ensuing presentation were the map legend, scale bar, north arrow, and inset (locator) map. Joy reminded us that the convention of north-oriented maps is not self-evident or universal, referring to medieval Christian maps (east-oriented – a worldview crystallized in the very concept of ‘orientation’) and south-oriented early Islamic and Chinese maps. A more recent south-oriented map is the McArthur’s Universal Corrective Map of the World, from Australia, published in 1979.

Having armed us with the basic knowledge we needed, Joy invited us to consider an array of maps she had been presented with in her editing practice. All of these maps were in need of improvement to make them clear for the reader. Often they lacked one or more of the basic elements discussed above. We considered maps with no legend, for instance, or where the legend assumed knowledge that the reader might not have (e.g. an unexplained ‘NAP’ in a map of the elevation of the Netherlands: a participant enlightened us with the correct English translation ‘Amsterdam Ordnance Datum’). Many maps relied on unexplained assumptions, like a colour-coded system of gradations from green (good) to red (bad), or a system of darker colours to indicate intensity, without providing a clear legend. In some cases, simply changing the orientation of a map or adding a scale bar could immediately make the map more informative.

In other cases, Joy had uncovered more complex issues, such as a map referring in the legend to 17 sites, but only actually showing 13, because ‘some symbols overlap due to the proximity of the sites’. Here Joy had advised the author to use a ‘callout’: a line from the symbol in the map to further explanation in a text box. Other delicate matters Joy has had to advise on included a map of the Wadden Sea and adjoining countries, in which the German state of Schleswig-Holstein had been shown as belonging to Denmark. In all, the message was not to take maps at face value when editing.

In the final section of her talk, Joy discussed the broader issue of the political implications of maps, neatly summarized in a quotation from El País (English edition): ‘Maps are not innocent drawings’. Here Joy touched on recent moves to replace the Mercator projection traditionally used in cartography with the more realistic ‘Equal Earth’ projection. The latter shows countries and continents in their true proportions: Africa, for instance, is much larger than the Mercator projection would suggest. But new maps can also reflect more sinister political aspirations. Joy pointed to the inset map that Chinese researchers are obliged to include in all their maps of China: when enlarged, this apparently ‘innocent drawing’ can be seen to designate Taiwan and other islands as Chinese territory, in contravention of the UN-agreed boundaries.

All in all, Joy’s presentation gave us plenty of material for discussion. At one point we considered the differences between a ‘contour map’ (terrain indicated using contour lines) and a ‘relief map’ (visual representation of terrain). I feel that Joy’s talk as a whole filled in the gaps in my very blurred and sketchy concept of a map, and made me more aware of maps’ potentially serious implications.

|

Blog post by: Maria Sherwood Smith |

By Percy Balemans, 13 October 2025

Some clients may ask you to ‘transcreate’ or ‘adapt’ a text instead of translating it. But what is transcreation?

Transcreation basically means recreating a text for the target audience, in other words ‘translating’ and ‘recreating’ the text. Hence the term ‘transcreation’. Transcreation is used to make sure that the target text is the same as the source text in every aspect: the message it conveys, the style, the images, the emotions it evokes and its cultural background. You could say that transcreation is to translation what copywriting is to writing.

One could argue that every translation job is a transcreation job, since a good translation should always try to reflect all these aspects of the source text. This is of course true. But some types of texts require a higher level of transcreation than others. A technical text, for example, will usually not contain many emotions and cultural references, and its linguistic style will usually not be very challenging. However, marketing and advertising copy, which is the type of copy to which the term transcreation is usually applied, does contain all these different aspects, making it difficult to create a direct translation. Translating these texts therefore requires a lot of creativity.

In her book on transcreation1, Nina Sattler-Hovdar explains the difference between translation and transcreation as follows: a translation is mainly intended to inform the reader, whereas a transcreated text must motivate the reader (for example to buy a product or service).

Required skills

In addition to creativity, a transcreator should also have an excellent knowledge of both the source language and the target language, a thorough knowledge of cultural backgrounds, and be familiar with the product being advertised, while at the same time being able to write about it enthusiastically. In addition, it certainly helps if the transcreator can handle stress and is flexible, since advertising is a fast-paced world and deadlines and source texts tend to change frequently.

Types of texts

The types of texts offered for transcreation vary from websites, brochures, and TV and radio commercials aimed at consumers to posters and flyers for resellers. They could be about any consumer product or service: digital cameras, airlines, food and drink, clothing and shoes, and financial products. Transcreators are often asked to deliver two or three alternative translations, especially for taglines, and a back translation (a literal translation back into the source language), to help their client, who typically does not understand the target language, get an idea of how the message was translated. Transcreators are also expected to provide cultural advice: they should tell their client when a specific translation or image does not work for the target audience.

What makes transcreation difficult?

In addition to the difficulties posed by creating a target text containing all the aspects of the source text (message, style, images and emotions and cultural background), marketing and advertising copy often poses other difficulties for the transcreator as well. Taglines, for example, often contain puns or references to imagery used by the company. They tend to be incorporated in a logo or image, with limited space and a fixed layout for the text. In addition, they are often used for multiple target groups: not just consumers, but also resellers and stakeholders, which means the text should appeal to all of them.

Can transcreation be done using AI?

If the Big Tech people are to be believed, AI can do ‘anything’. The AI tools used for translation and related tasks consist of so-called large language models (LLMs). LLMs are algorithms that basically ‘link together word patterns they’ve calculated from their training data’2. LLMs do not understand language, so they do not write texts – they simply combine words based on algorithms.

An LLM could potentially be used for brainstorming, but using them to try and transcreate a text is not recommended, as they do not understand cultural references, idiom or word play. They may get it right in the case of commonly used references, but it is not safe to rely on this. Creating a customized transcreation for a specific target audience still requires the skills of a professional human translator.

Also, doing your own research by browsing dictionaries, thesauri, and other trusted sources, instead of getting answers from a machine, stimulates your creativity and helps you find plenty of creative options.

Sources

1. Get Fit for the Future of Transcreation: A handbook on how to succeed in an undervalued market by Nina Sattler-Hovdar.

2. The AI Con: How to Fight Big Tech’s Hype and Create the Future We Want by Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna.

|

Blog post by: Percy Balemans |

By Paula Arellano Geoffroy, 25 September 2025

Former lawyer and legal translator Tom West joined SENSE in May this year. He is a certified translator from French, Spanish, German and Dutch into English, and is a former president of the American Translators Association (ATA). I reached out to him to ask about his background, and about the key to translating so many languages. Below you will find his interesting answers.

Former lawyer and legal translator Tom West joined SENSE in May this year. He is a certified translator from French, Spanish, German and Dutch into English, and is a former president of the American Translators Association (ATA). I reached out to him to ask about his background, and about the key to translating so many languages. Below you will find his interesting answers.

I understand that you are American but have now settled in Amersfoort. Can you tell us a bit about your background and why you decided to move to the Netherlands?

I had always dreamed of living in Europe, and following an unwanted and painful divorce, I decided to make the move. It turns out that there is a Dutch-American Friendship Treaty that makes it rather easy for an American to get a visa to work as an entrepreneur in the Netherlands. I moved here in February of this year and had my verblijfsvergunning in my pocket six weeks later. The efficiency in this country is impressive.

How was your experience as president of ATA?

I had the privilege of serving as president of ATA in the early 2000s, when the profession was growing by leaps and bounds. It was an exciting time. Unlike the situation in Europe, there are very few schools that offer degrees in translation (or even training for translators) in the United States, so I made it my task to invite as many experts as possible to our conferences so that working translators could get the training they desired and couldn’t find elsewhere. There were so many people joining the profession at the time that we were able to offer specialized conferences on legal or financial or medical translation in addition to our large annual conference. A wonderful byproduct of the experience was that my predecessor, Ann Macfarlane, under whom I served two years as president elect of the association, is a natural leader and teacher who taught me a lot about servant leadership and how to run an effective meeting. Those lessons from Ann have stood me in good stead ever since.

Of all the languages that you master, which are your preferred ones? How did you learn them?

That’s sort of like asking me which of my children is my favourite. I can’t answer it because I’ve never really met a language I didn’t like. But I can tell you about my experience with each one. At some point in my childhood my mother happened to tell me that people in other countries speak differently than we do, that they even have completely different languages! For reasons I still don’t understand, I was so fascinated by that idea that I wanted to learn as many languages as possible. I grew up in a monolingual English-speaking family in a part of the US where most people trace their ancestry to the UK, so hearing or speaking other languages first-hand wasn’t a possibility, but my parents gave me their high school French and Spanish textbooks from the 1950s, and I set about studying them – although it felt more like play to me.

I took French and Latin in high school, spent a summer in Mexico supposedly teaching English but actually learning Spanish, and then started studying German and Russian at university. I majored in French and went on to get a master’s in German – switching gears, so to speak, because I couldn’t decide which language I liked better. I taught first-year German at the university where I did my master’s and then spent two years teaching French and Spanish at a secondary school. But I began to grow restless, so I set off for law school and obtained the Juris Doctor degree, was admitted to the Bar and practiced law at a large firm for five years. But I still wanted to study languages all the time, and even the evening courses in Dutch and Swedish I attended at a sort of volksuniversiteit in Atlanta were not enough. In the meantime, other lawyers at the firm began asking me to translate legal documents for them in addition to my regular legal work, often because they had already received an unusable translation from a local translation agency. I found that work even more interesting than drafting contracts, and after five years, I decided to try my hand at being an entrepreneur. So I left the law firm and started my own translation agency specializing in legal translation. Over the years I put together a fine team of other lawyers who had left the law to become legal translators along with other translators who specialized in legal documents. The company ultimately grew to over a million dollars in revenue, and we were known not only in the US, but also particularly in the Frankfurt market in Germany for the quality of our translations.

Because I have always been a collector of words, at the outset of my translation career I started recording the terminology that I had researched, especially because I find comparative law so interesting. One of my first clients was a large law firm in Miami with clients all over Latin America, so for example, we would receive documents from Guatemala on Monday, Argentina on Tuesday, Mexico on Wednesday, Costa Rica on Thursday and Ecuador on Friday. It is uncanny how much the legal terminology differs from one Latin American country to another, and back in those pre-Internet days, I travelled to law libraries in Latin America and at US law schools to research puzzling Latin American legal terms that had not made their way into any of the reference works. In 1999 I published the first edition of my Spanish-English Dictionary of Law and Business (the third edition of which will appear later this year), and I believe that if I have made any contribution at all to my chosen profession, this is it. The dictionary has been a bestseller, not only among translators, but also among lawyers working in the Latin American market. Over the years, I have also published the Trilingual Swiss Law Dictionary (Swiss French into German and English, and Swiss German into French and English) – because I found Swiss legal terminology in German so opaque – and also the Swedish-English Law Dictionary – because I did a lot of work from Swedish to English at one point. A visit to the Netherlands several years ago resulted in a large multi-year project for Aard van den End, vetting the entries in his famous ‘Juridisch Lexicon’. That took me deeper into Dutch legal terminology, and because the lexicon translates Dutch into both English and German, it became a fascinating three-way exercise in comparative law, often with Belgium thrown into the mix, making it a four-way game (Belgian law is sometimes more like French law than Dutch or German law). I can’t get enough of that, and still read comparative law books for fun.

I should also mention that I fell in love with Afrikaans before a trip to South Africa in 2016, and since my move to the Netherlands, I’ve attended Afrikaans classes at the Zuid-Afrikahuis in Amsterdam. I particularly like Afrikaans poetry and find it a joy to speak and listen to, but it certainly creates a lot of interference with my Dutch!

What kind of projects are you currently working on?

As I said, I’m a collector of words, and I love lexicography, so I am currently putting the finishing touches on a new ‘French-English Dictionary of Law and Business’, as a companion to the third edition of my ‘Spanish-English Dictionary of Law’, both of which I hope to publish this year. I continue to translate court documents, most often from French, Spanish or German into English. That’s the kind of text I enjoy the most because it allows me to put my legal training to its best use. I continue to teach legal translation online. And I’m working on my Russian by taking lessons on Italki.

What is your take on AI and translations?

I’m afraid that a lot of the legal translation market began to dry up with the introduction of DeepL in 2017, and my impression is that lawyers began using it in droves, particularly because it produces a translation in a matter of minutes. For example, many or even most of the contract translations into English we used to prepare were for information purposes only, because only the original untranslated version was going to be signed and would govern. The speed desired and the lack of a need for complete accuracy have made DeepL and other programs a game changer for lawyers (and did I mention that these translations are available for free or next to nothing?). Fortunately for our profession, I find that DeepL is much less able to translate court documents accurately, so there is still a market for that. As for AI, I feel certain that lawyers are using it for translations as well, but I am less familiar with how well AI handles legal documents. I do find ChatGPT strangely inaccurate when I ask it questions about law in other countries.

How did you learn about SENSE and why did you decide to join?

Earlier this year, I attended a meeting in Vienna of the ATA German Language Division in Europe (GLD-Europe). There I had dinner with my long-time colleague Dr. Karen Leube, who lives in Aachen. She has been head of the GLD and a member of SENSE and she advised me to join SENSE right away – which I did!

What do you enjoy doing in your free time?

My passions other than languages are music, travelling and reading. I wasted no time joining a local choir when I moved to Amersfoort and have loved it, not least because we sing in Dutch, German, French and English! I have to admit that I miss my piano, which is in storage back in the US. One of the most wonderful things about finally living in Europe is that I can attend concerts and other musical events so easily. In July I attended a ‘sing-along’ in London with the great British composer John Rutter – and believe me, it is much easier to take the Eurostar from Amsterdam to London for the weekend than to fly from the US to Heathrow! And I delight in the fact that I can check the concert schedule at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam and be there in less than an hour – and in five hours, I can even be in Berlin for a whole weekend of music.

Are you a good reader? Have you read something interesting recently?

I love to read and usually have several books going at once. Currently, I’m reading ‘Wisselwachter: Amerika-Europa 1933-1945’ by Geert Mak, which I highly recommend. I’m about halfway through ‘Wir Kinder des 20. Juli’, by Tim Pröse, which is important to me because one of my friends in Germany is the granddaughter of one of the leaders of the plot to assassinate Hitler on 20 July 1944; he was hanged at Plötzensee for his participation in the conspiracy, and his wife (my friend’s grandmother) was sent to a concentration camp, where she fortunately survived. In English I’m reading Katja Hoyer’s ‘Beyond the Wall: East Germany 1949-1990’. So you can see that I read almost exclusively nonfiction and am particularly interested in history. But last fall, while still in the States, I participated in an online Russian reading group where we read ‘Anna Karenina’. I had never read it, and despite my general lack of interest in fiction, I found it beautifully written and very compelling. So I may well pick up another work of fiction one of these days.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy |

By Susan Jenkins, 10 September 2025

Intelligent Editing recently released a new version of Draftsmith, the AI-supported editing tool that I reviewed in March 2024. Back then, generative AI tools for working with texts were announced on almost a daily basis, but were still early in the adoption phase by everyday users. Since then, we’ve moved past questioning whether generative AI is going to make much difference in our daily lives. Understanding how to work with it is becoming an essential skill.

Purpose-built tools make adoption easier by reducing the time needed to craft skilful prompts for generative AI chatbots. Remember a time when you bought something you had to assemble yourself, with your own tools, before you could use it for its intended purpose? Did you wish for a complete, ready-to-use item out of the box?

Draftsmith initially launched with a broad selection of ready-to-use tools called ‘suggesters’ aligned to different editing contexts. It took some experimentation to learn which suggesters were suitable for my many wordsmithing hats, but the results were more reliable than when using a Large Language Model (LLM) chatbot. It was also a bit speedier than my unassisted editing process. Draftsmith 2.0 makes the revising process even smoother by improving the flexibility and navigation of the software. They’ve also added a better tutorial on their site.

On the back end, they’ve improved the quality of suggestions by switching to one of OpenAI’s small language models more suited to writing, which also makes Draftsmith’s processing faster.

In my review of the first version, I sampled its arsenal of suggesters to address the various style, audience, or readability aspects that editors pay attention to. For this update, I again tested a few different texts from my workflow: a magazine article, a furniture catalogue, and a research article by a non-native English speaker.

The main feature that’s changed in Draftsmith since version 1.0 is the editing window and the amount of text it processes. Instead of displaying one sentence at a time, it now analyses a whole paragraph. Sentences from the paragraph appear in the ‘decision box’ with suggested changes. Just as in version 1.0, you can toggle the view to see or hide changed text, but there are more options to support your workflow.

Each sentence in the paragraph appears framed between a purple bar on the left and green bar on the right. Purple resets the text to the original, while green generates a new version. You can use these respectively to either reject an edit or regenerate a new one. These functions work on both desktop or tablet devices by using either a mouse, touchscreen, or keyboard to swipe or click for the desired action.

Rejecting an edit with a mouse click (before and after clicking)

Sometimes you like only part of a suggestion, so Draftsmith allows you to tweak the suggestion manually. Simply double-click on a sentence in the decision box and insert the cursor where you want to type, just as you would in the main document.

Once you are happy with all the sentences in the paragraph, click the ‘accept all’ button. Draftsmith will update the document and move to the next paragraph. If you have track changes active, these will be highlighted – another new addition to the software which gives editors more control. By analysing whole paragraphs instead of sentences, you also move through a document more quickly than before.

The new version isn’t without some hiccups. When using the Word Count suggester on quoted text, it sometimes edited the punctuation at the end of sentences unnecessarily. In fact, quoted statements are not always ignored for cuts or word changes, which hampers editing in texts with interview subjects. Draftsmith’s engineers are considering a setting for this in a future version.

Something that hasn’t changed is Intelligent Editing’s customer-centred approach to development. As I wrote in the first review, they are keen to support a very specific group – human editors – and their skills and pain points. While there are hundreds of products on the market for writers and editors claiming AI productivity gains, this company was trusted in the field long before anyone ever thought to connect an LLM with a chatbot.

|

Blog post by: Susan Jenkins |

By Claire Bacon and Tomas Brogan, 25 August 2025

Claire’s account

A lot can happen in ten years. On 21 June, language professionals met in Amersfoort for the SENSE 35-year Jubilee conference. This was ten years after my very first SENSE event – the 25-year Jubilee at the Paushuize in Utrecht – so I was feeling a little nostalgic. Back then I was a fledgling language professional in the early stages of transitioning from lab-based research to at-home editing. Now – thanks largely to some great people I met through SENSE – I am a successful scientific language editor and scientific writing trainer with plenty of work. At least that’s the story I would be telling if we had celebrated the SENSE Jubilee two years ago! A lot has changed in the industry in the last few years and it is putting a strain on all of us.

The challenges facing our profession were, not surprisingly, the main topic of the day. Jackie Senior defined these challenges in her presentation of the results on her survey on what SENSE members think about the rise of AI and how it is affecting our jobs. Apparently our response to AI has not been overwhelmingly positive. Far more of us are feeling apprehensive rather than positive about AI, and half of us have seen a drop in our income. Jackie’s tips to future-proof our language businesses included upskilling and diversifying, with a focus on doing what you enjoy and valuing your time. Jenny Zonneveld also talked about how we can survive AI by thinking like an entrepreneur and increasing our visibility, for example by attending conferences, volunteering, and sharing useful content on social media. One thing that struck me, attending the presentations and chatting to people, is how much we care about what we do – and how good we are at it! Although the sense of doom and gloom is undeniable, we are not ready to give up just yet. We know that we offer valuable services to our clients and cannot truly be replaced by AI.

After Jackie and Jenny’s talks on surviving AI, I took a welcome break to focus on my physical and mental well-being. Anne Hodgkinson and Monique ten Boske showed us a series of yoga and tai chi moves that we can do at our workplaces. The beauty of these moves is that they benefit the mind as well as the body, helping us to concentrate better while combating the aches and pains associated with too much sitting. That’s something we all need! Next came Ana Carolina Ribeiro and her talk on rebranding. Ana had recently successfully rebranded herself as a translator and copywriter working with Brazilian Portuguese and used her own experiences to give us an effective seven-step strategy to the rebranding process. She also encouraged us to think carefully about whether we need to rebrand or not (apparently it is far from simple!). Through her questions, she helped me to realize that a rebrand could be just what I need. I had not completely realized it, but I am moving further away from basic copyediting of scientific articles (that AI can do) and focusing more and more on structural editing (that AI will probably mess up seeing as it can’t think!) and teaching. This shift in services and focus means a rebrand is on the cards. Finally, Marieke Krijnen gave an engaging talk on interventions that improve the clarity and readability of scientific articles. Marieke presented sentences that had appeared in papers she had edited, diagnosed the problems with these sentences, and then showed us how she solved these issues for her clients. This prompted plenty of ardent feedback from the audience!

As always, it was an absolute pleasure to mingle with my SENSE colleagues for a day. It gave me the chance to catch up with old friends and meet new ones – including my colleagues on the Content Team, who I have been working with for years but never actually seen in person! Such are the joys of in-person networking. It was a thoroughly enjoyable day and I am already looking forward to the next event!

Tomas’ account

On Saturday 21 June young (at heart) SENSE members and guests gathered in Amersfoort to mark the 35-year Jubilee. Kicking off with an enlightening session on future-proofing your business by Jackie Senior, SENSE members got a breakdown of survey results concerning, among others, member’s attitude to AI: are they curious, avid, or willfully ignorant of AI’s supposed powers? Jackie’s talk led nicely into Jenny Zonneveld’s even more wide-ranging take on the broader economic outlook, from geopolitics down, with a focus on the thorny question of how – or indeed whether – to integrate AI into work processes. Meanwhile, in the other room Michael Friedman shared his expertise on legal citation.

After a tasty lunch, there was the choice between two contrasting talks: how to improve writing and translation processes by Simon Berrill, or an introductory yoga and tai chi session. For most, the choice was obvious and immediate and both sessions were very well received.

Later, the Unconference session run by Lloyd Bingham was a valuable introduction to the concept for the uninitiated. The subjects were decided on by the group and led to a lively and respectful exchange of ideas around the ever-present theme of pricing and an accompanying emphasis on core freelance business skills.

After a short break, Marieke Krijnen led a somewhat riotous and thoroughly enjoyable session looking at copyediting interventions that improve clarity and readability, while Courtney Greenlaw gave a wonderful talk on fantasy, translation and the use of digital tools.

After a short break, Marieke Krijnen led a somewhat riotous and thoroughly enjoyable session looking at copyediting interventions that improve clarity and readability, while Courtney Greenlaw gave a wonderful talk on fantasy, translation and the use of digital tools.

Attendees then returned to the canteen for a plentiful dinner and a well-received speech by new Chairwoman Liz Cross, before wrapping things up with a zesty Crema Catalana.

All in all an enjoyable day with great food and plenty of opportunities to chat and network.

|

Blog post by: Claire Bacon |

|

Blog post by: Tomas Brogan |