Ever since becoming SENSE Content Manager I’ve been wanting to write about the history of our Society and the composition of its membership. So I spoke to founding members, did a deep dive into our website archive, and downloaded our membership database, and I am happy to share my findings here and in a follow-up article about SENSE demographics.

The prelude to SENSE’s creation took place in 1989, when a group of 20 English-speaking people working as freelance editors in the Netherlands began meeting informally in Wageningen and Zeist under the name of the English Native-Speaking-Editors Network (ENSEN). In 1990, the group changed its name to The Society of English-Native-Speaking Editors (SENSE) and was formally registered at the chamber of commerce in The Hague. At its first General Meeting in Baarn, with 35 members, the first Constitution was ratified and an Executive Committee was formally elected. The late Peter Attwood became Chair, and the current Honorary Members Joy Burrough and Jackie Senior became Secretary and Treasurer.

A name and a meaning

In the following year, a contest was held to create a logo and a distinctive acronym. In the logo, an ellipse surrounds the word ‘sense’, which carries a caret under the letter ‘e’. A caret (^) is a symbol used by copy-editors and proofreaders to indicate a proposed insertion in a text when marking up texts manually or on paper. Both the ellipse and the caret signal the meticulous editing of the word ‘sense’, which at the time represented the name of the Society, but today is written SENSE. Not long after, the leadership chose to use orange and blue as the Society’s distinctive colours.

Growing

During its first decade, SENSE grew to 170 members. The Society began producing a quarterly newsletter printed on A4 sheets, held its first copy-editing training workshop, and launched an electronic Forum in which members could interact with each other and ask for help regarding anything related to their various language-related fields of work.

Becoming digital

SENSE continued its foray into the digital era with the launch of its first website in 2001 and four years later with the first digital newsletter called ‘eSense’, which was replaced in 2018 by a Newsletter and a Blog. In 2010, almost a decade after its launch, the website was upgraded to a content management system (CMS) for publishing website content. In 2016, SENSE’s website was updated with the modern ‘look and feel’ that it has today, and at the same time the Society became active on social media, creating and sharing content on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter (currently X).

Diversifying

By early 2017, SENSE had grown to be a larger, more diverse and open institution. The Society modernized and updated its Constitution with an inclusive policy that welcomed and allowed voting rights not only to English-native speakers but to all English-language professionals in general, and changed its official name to ‘SENSE the Society of English-language professionals in the Netherlands’.

A mission and a strategy

SENSE’s mission reads, ‘We want to make sure that all SENSE members, both new and existing, are aware of all the resources SENSE has to offer to help them improve their professional skills and increase their professional networks. In addition, we want to encourage as many members as possible to actively participate in SENSE to both share their knowledge and experience and to learn from each other.’

The Society strategy for 2022‒2024 states the following goals:

- To bring English-language professionals into contact with each other.

- To provide a resource network of skills, specializations and experience.

- To encourage communication between societies and institutions involved in publishing commercial, technical and academic material in the English language.

Nowadays, SENSE represents a diverse group of roughly 280 members, encompassing translators, editors, proofreaders, copywriters, journalists, trainers, language teachers, subtitlers, interpreters, transcribers, indexers, technical writers, and content writers. There are 20 languages represented in the Society, with 88% of members living in the Netherlands and 12% living abroad. But if you want to know more, all these interesting figures will be discussed in more detail in an upcoming post titled ‘SENSE demographics 2023’.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy Website: paulaarellanogeoffroy.com LinkedIn: paula-arellano-geoffroy |

Editor, proofreader and translator Heather Sills (website: www.heathersills.com; LinkedIn: heathersills) joined SENSE in July 2023. I invited her to tell us about herself and her life in the city of Ghent in neighbouring Belgium. She accepted with enthusiasm and here is what she said.

Editor, proofreader and translator Heather Sills (website: www.heathersills.com; LinkedIn: heathersills) joined SENSE in July 2023. I invited her to tell us about herself and her life in the city of Ghent in neighbouring Belgium. She accepted with enthusiasm and here is what she said.

Can you tell us a bit about your background and where you are from?

I was born and raised in Norfolk in the UK, before heading to Durham University to study Modern European Languages and Cultures. This included a year abroad, during which I was an intern for a translation agency and a hotel booking website in Berlin. After I graduated, I moved to London, where I got my first ‘real’ job as an editor for a tourism website, part of the renowned Frommer’s Travel Guides. From there, I moved to Thomas Cook, where I managed the hotel content. I then took a bit of a sidestep by becoming the product owner for an in-house content management system. Everything I’d learnt about how to create, edit, translate and maintain content went into being the business representative, working in IT, putting forward requirements, testing and giving feedback on new functionality, and managing projects end to end. This explains why a lot of the books and other texts I now translate and edit are on business and IT topics, as well as on tourism/travel and global development issues.

What brought you to Belgium?

When I was working in London, most of the software development team were based in Ghent. So, I was living out of a suitcase, travelling back and forth on the Eurostar. Eventually, I realized that after eight years in London it no longer felt like home. And I absolutely loved Ghent – it was the picture-perfect, café-strewn, cobblestoned town that I’d always dreamt of living in. It made me feel European again. So, I asked if I could be based in Ghent for a year. My boss agreed, I packed a slightly bigger suitcase, and – eight years later – I’m still here!

Belgium has three official languages: Dutch, French and German. Do you speak all of them? Do you translate all of them?

I spoke German fluently when I was in Berlin. So, when I started trying to pronounce Dutch, everyone thought I was German, which led to some fairly amusing conversations… But after studying it at Ghent University and throwing myself into the deep end by working at a software company with no other internationals (quite rare in Ghent these days), I’m now told I speak Flemish like the proud Gentenaar that I am!

The main language I translate from is Dutch, as a lot of my clients are based in Flanders or in the Netherlands. But I also translate from French (mainly for clients from Brussels who’ll send you a jumble of Flemish and French without even realizing it) and from German. A lot of the English-language texts I edit are written by native Dutch speakers. I think it helps to know the language they were thinking in when they wrote it. It makes it much easier to work out what they were trying to say and then you can rewrite it in a more natural way.

You’ve been working for different companies for a long time, but a few years ago decided to set up your own business. How is that working for you? Do you like freelancing?

Indeed, I’d been translating and editing in my spare time ever since I was a student, but as I climbed the ladder in my day job, I realized I was spending too much time in meetings and not enough time doing what I really enjoyed. It was actually the coronavirus pandemic that gave me the push I needed. I noticed that companies were much more open to using freelance staff working remotely. After all, everyone was working from home. So, I quit my job and started offering translation and editing to clients around the world. There have been plenty of ups and downs, but each one has taught me something new. I love that I get to work on some wildly different topics and for all kinds of companies, from start-ups to publishing houses to government institutions and universities. No two weeks are the same. Plus, there are far fewer meetings…

Do you have any preferred hobbies?

Unsurprisingly perhaps, I like anything to do with languages and for me a big part of that is travelling and experiencing the country of the language you’re learning. Languages aside, I also love cooking and I am very interested in nutrition, fitness and well-being.

How did you learn about SENSE?

A fellow translator posted a link to a SENSE event in one of the Facebook groups I’m in. Even though I don’t live in the Netherlands, I thought it would be a useful organization to join. As far as I’m aware, we don’t have an equivalent in Flanders or anywhere in Belgium.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy Website: paulaarellanogeoffroy.com LinkedIn: paula-arellano-geoffroy |

SENSE Professional Development Day 2023

Written by Jasper Pauwels and Tomas Brogan

On Saturday 30 September, SENSE welcomed members and guests for their first in-person Professional Development Day (PDD) since 2019. Held in Park Plaza hotel in Utrecht on the Feast Day of Saint Jerome – the patron saint of translators – language professionals were greeted by the Room Angels, also known as the organizing team: Maaike Meijer, Naomi Gilchrist, Nandini Bedi, Kerry Gilchrist and Lizzie Kean, who showed everybody to their meeting rooms throughout the day.

The organizers put together a diverse programme of workshops and presentations, and there was something of interest for everyone. Attendees were welcomed with coffee, croissants and cake, in addition to a well-received buffet lunch, which gave everyone time to mingle.

Below are some session recaps. If you log in to our website, you’ll find an overview of all the workshops on the 2023 PDD conference page.

Editing slam

Editing slam

Copy-editor and English teacher Nandini Bedi and copy-editor and proofreader Danielle N. Carter invited attendees to edit a humanities text written in English by a German scholar. This made for a lively interactive session.

The text was both poorly written and poorly organized, making it difficult to read and make sense of. Besides considerations such as changing the voice, e.g. from ‘this paper attempts to show’ to ‘I will show’, other issues were considered alongside the question of how far the text should be reorganized.

It was recommended that the editor request a sample of the source text before accepting an editing job. If the budget is tight, you may have to work out your client’s priorities and do less research. When giving feedback, you should strive to write cordial – but brief – comments to double-check with the author if your changes are acceptable and that the edit still reflects the intended meaning.

Attendees were particularly interested in the use of various software to speed up the editing process, in particular the Word plug-ins PerfectIt and Editor’s Toolkit Plus, together with macros such as JoinTwoWords, DocAlyse and HyphenAlyse. The Read Aloud function in Word was much praised by Nandini because it allowed her to check the flow of the text without the distractions of track changes. Another tip from Danielle was to rewrite various clients’ style sheets in your own standardized format for speedy reference.

Last but not least, the presenters and audience reflected on the crucial importance of communication outside of the editing process. For example, the presenters cautioned against contacting the author of a particularly troublesome piece for more information since lengthy email correspondence is not included in your quote. They trust your expertise and want you to make the text look respectable. To stress this, Nandini delivers work with the word ‘final’ in the filename.

Grammar & punctuation refresher

We can think of less intimidating things than presenting grammar and punctuation tips to professional language nitpickers, but Bristol-born Dutch-to-English translator Claire Niven executed the task with panache. The first part of the presentation focused on punctuation, with a strong attention to comma use, while the second part was about changing language conventions, such as singular ‘they’ and spelling issues related to race and ethnicity.

Claire covered four basic commas: the listing comma, the joining comma, the bracketing comma and the introductory comma, as well as the order of adjectives, which can be tricky. Native speakers subconsciously know the right order: determiner, observation or opinion, size, shape, age, colour, origin, material, and, finally, qualifier. If you would like to understand why ‘silver small spoon’ just does not sound right, you might enjoy reading ‘The Elements of Eloquence’ by Mark Forsyth.

Commas were just one of the language-related subjects that sparked a lively discussion. Hearing people’s different opinions and experiences helped those present to take more informed decisions on a variety of issues as the Oxford comma, the distinction between ‘which’ and ‘that’ in subordinate clauses and the singular ‘they’.

Race and ethnicity are hotly debated topics in contemporary societies and spelling can play a bigger role than you might think. Claire discussed capitalizing ‘Black’ (but not necessarily ‘White’), and noted that the term ‘Caucasian’ stems from outdated biological theories about race. ‘Person of colour (POC)’ is not as common in British English as in American English today, but like much of what we discussed, that may change in time. A highly recommended website in this regard is ‘The Conscious Style Guide’.

Transcreation

Despite facing technical difficulties, transcreation specialist Branco van der Werf delivered a captivating presentation in his own unique style on finding and keeping transcreation clients. Having specialized in translating creative marketing copy since 2014, Branco generously shared his insights from his chosen niche.

First and foremost, budding transcreation translators should not call their services transcreation, because that is what translation agencies call it. In Branco’s opinion, working on transcreation projects through translation agencies is not ideal. If you would like to work directly with marketers, you should search for marketing companies offering services called market internationalization, international copywriting or simply creative translation. Marketeers often specialize in either business to business (B2B) or business to consumer (B2C) marketing and you should consider which one suits you best, or whether you want to offer both. As a rule of thumb, B2B has a more corporate, objective style of writing, whereas B2C is more subjective and is about eliciting emotions.

When working with marketing agencies, it is vital not to undersell yourself. Focus on what is relevant to them – they are probably not interested in what computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools you use and probably assume that you are meticulous and will deliver on time. They are interested, however, in which marketing projects you have completed, and for which brands. Keep your first elevator pitch email to two or three lines to get them interested.

One effective way of keeping your new-found clients happy is writing memorable emails, and sharing your enthusiasm for the project and how it ties in well with your previous experience. Of course, high-quality translation – or ‘market internalization’ – makes every client happy. When translating taglines, give your client options to choose from, instead of rephrasing the same translation three times.

But being creative on demand can be hard if you have no inspiration. To get his creativity flowing, Branco likes to impose restrictions on himself, such as trying to rhyme, making the copy shorter or choosing a different grammatical subject. Puns and humour are another great avenue to explore. And even if you hate your own pun, it could put your creativity back on track.

How to write great copy

Business writing trainer Stephen Johnston gave a whistle-stop tour of what is normally a two-day workshop on copywriting in just 45 minutes.

This workshop was the epitome of ‘there is no try’ as Stephen quickly and skilfully wrangled copywriting issues out of attendees, which he marked on a whiteboard and revisited at the end of the presentation.

One of the main takeaways was that great copy needs to get into the reader’s head, and not just remain on paper. To do this, both general principles and specific ‘job aids’ can be used.

In general, write the way you talk. Talk about the benefits – and not your features – as a business or freelancer. Help the reader by providing short, goal-oriented, navigable copy that has a clear structure, good grammar and a strong take-home message. Other tips included the ‘rule of three’: stop, look and listen.

The importance of considering the order in which information is presented was emphasized, as well as using informational sub-headings (e.g. using ‘Sales increased by 50% in the 2nd quarter’ rather than just ‘Sales’).

In terms of job aids, SCOPE was the most important:

- Start – describe the reader’s current situation (that everyone can agree with).

- Change – introduce a problem to be solved.

- Overall question – identify the question posed by the change.

- Principal message – answer the question with a principal message.

- Explanation – briefly explain your supporting information.

In general, a masterful presentation with many actionable points for the audience.

Video game localization

If you think video games are for shy teenagers, think again. Video games are a multi-billion-dollar industry that is increasingly relevant to pop culture, just like cinema and music. Games go beyond entertainment and are also incorporated in e-learning, health and safety regulations, and to raise awareness on racism and cyberbullying. In his interactive and informative presentation, Melchior Philips, who has five years of experience as a video game translator, confirmed that many people prefer to play video games in their native language.

Everything in a video game has to be translated: from the characters’ dialogues and user interface to support materials and patch notes (technical notices on improvements in new updates) to texts about the game (online store pages, product descriptions and newsletters), and even terms of use and end-user licence agreements.

Most video games are produced in the US and Japan and often contain cultural references that warrant localization. You need a lot of creativity, especially since context and visuals are not always provided. For many game developers, translation is an afterthought. The lack of context is often countered by two rounds of quality assurance, one in collaboration with the developer to see if the translations work in the actual game, followed by a linguistic quality assurance with a reviewer.

Video game localization is hard work but good fun, and unfortunately, the fun is also reflected in the rates offered. Many video game translators will work with specialized translation agencies, which at least usually guarantees a steady flow of work.

Yoga while you work

Anne Hodgkinson was the last presenter with her yoga class, which was perfect timing after a long day of mostly sitting. Together, attendees tried a number of yoga exercises that can be easily squeezed in between tasks while working. Clearly, this was not the first yoga class Anne taught and with her skilled guidance, even complete novices experienced the beneficial effects of office yoga. Everyone’s body is different and you should always respect your limits, but some exercises were truly manageable for every language professional. Reinvigorated and relaxed, we headed down to the bar, knowing a few new ways to work more healthily and happily.

If you add Matthew Curlewis’ ‘Write to reconnect’, Anne Oosthuizen’s ‘Poetry and song translation’, Hanneke de Raaff’s ‘Music interpretation in sign language’, and Jenny Zonneveld’s ‘Creating an ergonomic workspace’, you’ll see that all in all it was a truly informative and splendid day.

Do you have an idea for a future online or in-person presentation? Or would you like to join the SENSE Continuing Professional Development (CPD) team? Please contact CPD@sense-online.nl.

|

Blog post by: Jasper Pauwels Website: www.pauwelstranslations.nl LinkedIn: jasperpauwels |

|

Blog post by: Tomas Brogan LinkedIn: tomasbrogan |

Conservation volunteering – Where work and leisure pursuits meet

Written by Hans van Bemmelen

I always used to translate Dutch into English, as that is what I am MITI-qualified to do. However, it seems that in recent years many into-Dutch translators have retired. Consequently one of my customers now regularly asks me to translate into Dutch – mostly operating manuals for mowers, chainsaws and other equipment used in the groene sector, the land-based trades, i.e. forestry, horticulture, groundskeeping, etc. As a conservation volunteer, I get to operate some of this equipment, chat with farmers and grounds personnel, and work with other volunteers from a wide range of backgrounds. As a result, my work and volunteering tend to support each other, making me more effective in both roles, and making both more enjoyable.

A number of years ago I joined an NLdoet volunteer work session in a park close to where I live in The Hague. I enjoyed that, so through a volunteering website I found the Werkgroep Agrarisch Natuurbeheer (WAN), which is active around Wassenaar and Leiden. The group manages geriefbosjes, coppices that used to supply farms with wood. Coppicing means regularly cutting trees back to stumps, after which they regenerate very quickly. This is done in winter when the trees are dormant. We mostly use an eight-year rotation, after which time the new shoots on the trees (ash, hazel, etc.) have grown to a height of six to eight metres and a diameter of around ten centimetres. It is essentially the same as pollarding where trees are cut higher up – knotwilgen being a key example in the Netherlands. Historically, coppiced timber was an important resource for the farms, providing both firewood and wood for tool handles, etc. However, as coppicing is very labour-intensive farmers have stopped doing it. Because copses can be an important habitat for a range of species, some are now looked after by voluntary groups such as WAN. We not only coppice and pollard trees but also plant new trees, dredge ditches, help install nest cameras, etc. Most of the work is done using pruning saws (pistoolzagen) which cut very quickly. We occasionally use chainsaws for heavier work and crosscutting the felled timber.

A number of years ago I joined an NLdoet volunteer work session in a park close to where I live in The Hague. I enjoyed that, so through a volunteering website I found the Werkgroep Agrarisch Natuurbeheer (WAN), which is active around Wassenaar and Leiden. The group manages geriefbosjes, coppices that used to supply farms with wood. Coppicing means regularly cutting trees back to stumps, after which they regenerate very quickly. This is done in winter when the trees are dormant. We mostly use an eight-year rotation, after which time the new shoots on the trees (ash, hazel, etc.) have grown to a height of six to eight metres and a diameter of around ten centimetres. It is essentially the same as pollarding where trees are cut higher up – knotwilgen being a key example in the Netherlands. Historically, coppiced timber was an important resource for the farms, providing both firewood and wood for tool handles, etc. However, as coppicing is very labour-intensive farmers have stopped doing it. Because copses can be an important habitat for a range of species, some are now looked after by voluntary groups such as WAN. We not only coppice and pollard trees but also plant new trees, dredge ditches, help install nest cameras, etc. Most of the work is done using pruning saws (pistoolzagen) which cut very quickly. We occasionally use chainsaws for heavier work and crosscutting the felled timber.

A few years ago I had to translate some chainsaw manuals so that was a good opportunity to do a course at IPC Groene Ruimte, a vocational training centre. Just as important as gaining technical knowledge and experience was chatting with the groene sector workers – basically the people who read the manuals I translate. Later, I also did courses on brush cutters and other equipment.

As the copses where I work are nearby farms, I get to chat with the farmers and learn about their work and equipment. That has been very useful in translating manuals for milking robots, tractors and flail mowers.

I also do some volunteering for Dunea, the drinking water company, which serves around 1.3 million customers in the west of Zuid-Holland and manages around 2,500 hectares of dunes that form part of the Nationaal Park Hollandse Duinen. Most of that work involves removing invasive vegetation such as black cherry (Amerikaanse Vogelkers) and white poplar (abeel) to preserve the openness of the dune landscape. These trees have to be dug out completely – cutting them would only cause them to grow back, as in coppicing. Again, chatting with Dunea staff and the other volunteers during coffee breaks can be very informative.

I also do some volunteering for Dunea, the drinking water company, which serves around 1.3 million customers in the west of Zuid-Holland and manages around 2,500 hectares of dunes that form part of the Nationaal Park Hollandse Duinen. Most of that work involves removing invasive vegetation such as black cherry (Amerikaanse Vogelkers) and white poplar (abeel) to preserve the openness of the dune landscape. These trees have to be dug out completely – cutting them would only cause them to grow back, as in coppicing. Again, chatting with Dunea staff and the other volunteers during coffee breaks can be very informative.

For me, combining conservation volunteering with working in areas such as agriculture and horticulture works really well.

|

Blog post by: Hans van Bemmelen Website: www.techtrans.eu LinkedIn: hans-van-bemmelen |

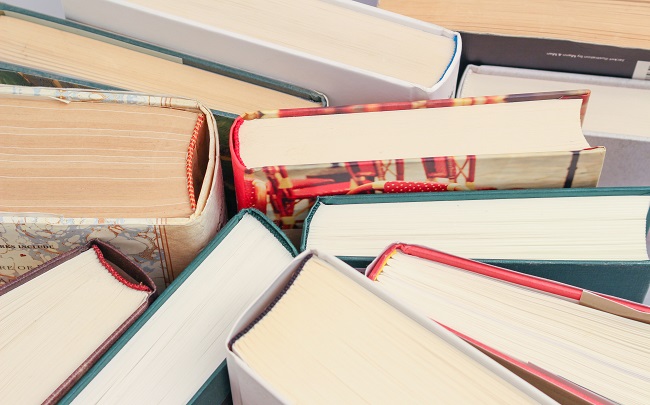

After a spell of inactivity, Southern SIG met again on 24 August via Zoom to talk about books and a whole lot more. The modest turnout (we were three) did not prevent a good list of book recommendations and, as we discussed during the meeting, a good recommendation can provide a great answer to the burning question of what to read next.

Client trouble

But first we discussed the thorny issue of a new client who had not paid their bill on time. You could send a disgruntled email, using words like ‘notice of default’, ‘collection fees’ and ‘statutory interest’, but that might not be your best option, especially if you enjoyed the project and wanted to maintain a good business relationship. Sending a few friendly reminders along with a more rigorous follow-up on future invoices might be a viable alternative, provided that you receive payment for the overdue invoice soon. The matter did have one surprising incidental discovery: some collection agencies provide webinars and masterclasses as a way of self-promotion. Attending one of these courses could allow you to brush up your business skills and terminology knowledge on this particular subject.

Shoulder pain and what to do about it

Something else you want to avoid is a frozen shoulder. Although bad posture is not the only cause, slouching behind your laptop all day is not going to help either. As we learnt from first-hand experiences, this affliction may result in some excruciatingly painful visits to the physio over a long period of time. So, mind your posture when sitting at your desk and consider buying a standing desk, but be advised that you also should not remain standing for too long either. Life’s complicated, isn’t it?

Books

We discussed quite a list of book recommendations, which you will find below in no particular order. Don’t worry if nothing tickles your fancy, because we have one bonus tip up our sleeves – former US president Barack Obama publishes his summer reading list every year, which includes both fiction and non-fiction. Hopefully, we have given you enough inspiration to warrant a visit to your local bookshop!

- ‘The Seven Moons’ by Maali Almeida: a dead photographer investigates his own death in Sri Lanka in the 1980s. Winner of the 2022 Booker Prize.

- ‘Cloud Cuckoo Land’ by Anthony Doerr, who you may know from ‘All the Light We Cannot See’: three interconnecting stories from the past, present and future.

- ‘The Patron Saint of Second Chances’ by Christine Simon: feel-good, light reading about a tiny Italian village that tries to allure tourists by spreading a rumour that a famous movie star is now living there – which is obviously not the case!

- ‘The Last Chairlift’ by John Irving, who you may know from ‘The World According to Garp’: a peculiar 800-page novel on transgenders in the early 1980s. Mostly interesting for Irving fans.

- ‘Demon Copperhead’ by Barbara Kingsolver: a modern-day David Copperfield story set in the southern Appalachian Mountains of Virginia during the opioid crisis.

- ‘Doughnut Economics’ by Kate Raworth: Oxford economist Kate Raworth explains an alternative economic model that respects the limits of what Earth can take while maintaining a basic standard of living for everybody.

- ‘Black Cake’ by Charmaine Wilkerson: the tale of a nurse moving from the West Indies to England and later on to America. Many family secrets will unfold.

- ‘War Light’ by Michael Ondaatje, who you may know from ‘The English Patient’: a coming-of-age novel set in London during the Blitz.

- ‘The Casual Vacancy’ by J.K. Rowling: a page-turner about trouble in the city council.

|

Blog post by: Jasper Pauwels Website: www.pauwelstranslations.nl LinkedIn: jasperpauwels |

Many SENSE members have benefitted over the years from the workshops and conferences for translators, interpreters and editors offered by Teamwork. Founded by Marcel Lemmens and Tony Parr in 1993, Teamwork has trained more than 3,500 professionals in the last 30 years. In this interview, Marcel and Tony tell us how their initial idea came to be and why the journey is now coming to an end.

It seems that you both share a love for languages – Marcel studied English at Tilburg and Nijmegen and Tony studied Dutch and French at Cambridge. Can you tell us a bit about your backgrounds and how you became professional translators?

Marcel: It was a bit of a coincidence, really. I was working as a teacher at a secondary school back in the 1980s when I realized that this was not a job that I was prepared to do for the rest of my life. I’d been in teaching for about four years and was enjoying the work when a colleague of mine – an excellent teacher – suddenly broke down from one day to the next. He never went back to teaching again. That’s when the penny dropped and I thought that I didn’t want that to happen to me. So I applied for a part-time job as a translator (‘vertaler/correspondent’ is what it said in the job vacancy) with a cigarette company in Zevenaar. I worked there for three years.

In the meantime, I graduated from the university of Nijmegen and also worked for the English publisher Collins both in Birmingham and in Doetinchem, where I lived at the time. The manager of the Collins Cobuild Dictionary had asked me to help his team of lexicographers design the grammar coding in the centre column of the first edition of the dictionary. It was one of the most thrilling jobs I have ever done. When I did a talk about my ideas on grammar coding in learners’ dictionaries at a lexicographers’ conference in Leeds, I met one of the two directors of the Translation Academy in Maastricht and he asked me if I could temporarily replace one of his lecturers who was on maternity leave. It seemed like a good idea. And that’s where I met Tony.

Tony: There was no proper study counselling at the bog-standard comprehensive school I went to in Oxford, and so – when it became clear that I didn’t have the right A-levels for doing a degree in maths – I decided to simply continue at university with the subjects I happened to be slightly better at at school: French and Latin. That was a big mistake. I dropped Latin as soon as I could, but also quickly became disenchanted with French. Studying French at Cambridge was a form of factory farming: the lectures were like a ‘megastal’ (a huge cattle shed) for students. I decided the time had come to do something different and, because my mother was a Flemish-speaking Belgian, it was Dutch I took up rather than Norwegian or Romanian.

Dutch was my saviour. It was brilliant. Just a small group of students, and lectures were ‘gezellige’ chats over coffee. I’m still in touch with the Dutch lecturer from my student days and will in fact be paying her a visit next week! However, despite having a go at modern and medieval Dutch literature, I felt rather embarrassed at the end of the course at my lack of good spoken Dutch. So I spent a summer working as a waiter in a hotel just outside Groningen and, after graduating, applied to all the Dutch universities for a job as a ‘studentassistent’ with the English department. Groningen was keen to have me, and so I spent two years there teaching drama classes to second-year students. It was great, but I didn’t really know much about English language or literature, so I thought I should move on.

I got myself a job as a translator with Vertaalbureau Bothof in Nijmegen (and just about every single English translator I have met in the Netherlands seems to have worked for Bothof at some point), where I spent three years under the tutelage of a truly brilliant translator, who taught me the tricks of the trade. I then spent a further five years working as an in-house translator for NMB Bank (now known as ING), before someone I met at a party invited me to apply for a job teaching translation in Maastricht. And that’s where I met Marcel.

How did the idea of creating Teamwork start?

Marcel: Teaching translation was great, but the vast majority of my colleagues in Maastricht had no practical experience as translators. That meant spending a lot of time translating newspaper articles, which were not only far too difficult for the students, but also totally unrepresentative. I had never been asked to translate a newspaper article when I’d been working as a translator.

Tony: Neither had I.

Marcel: And there were other things that grated. Not just the rather literary approach to translation, but the haphazard way in which texts were selected, the blindness to the type of material (often poor-quality) that real-life translators worked with, the marking system, and so on. Tony was a kindred spirit and we soon set about producing a handbook for student translators based on a totally new approach to translation techniques: ‘Handboek voor de vertaler Nederlands-Engels’.

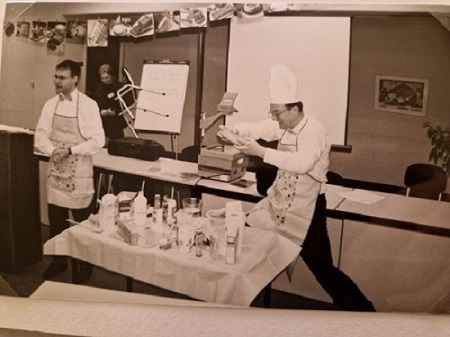

Tony: At some point in 1993, we decided to run a translation workshop for former students of Maastricht. It was very popular – probably something to do with the fact that we offered our ‘workshoppers’ a slice of local ‘vlaai’ (from Mathieu Hermans, of course) during the coffee break.

Marcel: So we did another couple of these workshops and opened them up to all comers. To our surprise, we found that people were willing to get up in the middle of the night and travel all the way from Enschede to Maastricht to attend a translation workshop. Never had our ‘flabber’ been so ‘gasted’.

Tony: It wasn’t long before we decided to move the venue to Utrecht, which was of course far more convenient for people coming from other parts of the country. And we gradually professionalized the way we worked, bringing in subject specialists and experienced translators from all sorts of different fields.

Did you become SENSE members at that time as well?

Tony: Yes, I joined SENSE in 1995, and Marcel joined a couple of years later. I can remember doing a number of workshops for SENSE members – for example, ‘Dunglish for beginners’ and other workshops on editing. We also did a talk called ‘Cookery for translators’ during which we outlined the thinking behind what was then our new handbook. This involved dressing up as chefs and doing disgusting things with flour and eggs.

It can’t always have been easy to run a successful business for 30 years. How has this journey been for you?

Marcel: For a long time, we were more or less the only people running workshops for professional translators. Things changed in 2009, when the government decided that interpreters in particular needed to work on a more professional footing. There had been a number of scandals involving court interpreters, and these led to the enactment of the Wet beëdigde tolken en vertalers, which placed an onus on registered translators and interpreters to undertake continuing professional development (CPD) on a regular basis. The number of operators offering courses for translators and interpreters mushroomed – a lot of them have since disappeared, mind.

Tony: Although we made it our business not to offer workshops especially for people looking to amass CPD points (and many of the new courses took the form of webinars given by subject specialists rather than hands-on translation workshops), the new system did of course affect our work in that it diluted the training market. We had previously branched out from English into other languages, but over the years we found that the number of takers for other languages began to decline. This first affected less common languages such as Russian, Portuguese, Turkish and Italian, but we gradually started to find it difficult to attract enough people even for French and German.

Marcel: English has never been a problem, though. English remains the backbone of the translation market.

Tony: And then came Covid.

Marcel: We were in the process of planning our last conference when Covid hit the Netherlands. We had to shut down everything for some time. After a while, we started offering in-person courses again, but the first few of these were subject to all sorts of restrictions and it was also clear that a lot of people were not prepared to travel or to sit in a room with other people, even if they were placed a long way apart.

Tony: We also decided fairly early on that we weren’t interested in going online. The type of courses we do are aimed at participation: there’s lots of discussion and interaction. I attended a few webinars to see how they worked and a lot of them proved to be no more than talking heads on Zoom, sometimes accompanied by old-fashioned PowerPoint slides (which often stayed on the screen for minutes at a time). It was clear that online courses needed a totally different approach – and a huge investment in technology.

Marcel: So we sat it out. The conference never came to fruition, but we got back to our traditional in-person courses in 2022.

So why are you closing down?

Tony: We’re both getting on. I’ll be 68 in January and Marcel turned 67 in September. I started receiving my state pension last year, after 42 years in the translation business. It’s time to call it a day.

Marcel: We’ve seen the translation market shrink and change in recent years. It’s clear that machines are going to take over part of the bulk market. There’s still going to be a call for ‘thinking translators’ – people who can use input in one language to produce a text in another language that appeals to readers and doesn’t read like a translation.

Tony: After 30 years, we think that we’ve said all we need and want to say: it’s not about translating all the words, it’s about producing good text.

Do you have any future projects?

Tony: For me, the future is going to involve even more rowing than I’m doing at the moment, as well as lots of travel and pottering around in the garden. The main thing is being free from diary commitments. It’s great not having to work.

Marcel: I still enjoy translating and editing, but more and more of my time these days is taken up with writing. In part, that’s copywriting for clients, but I’m also doing lots of original writing. I published a book called ‘Als je BGRPT wat ik BDL’ in 2020 (full of writing tips) and have just completed a new book called ‘Een andere kijk op lezen’. It dispels a number of myths about reading and about the much-heard claim that ‘no one reads any more’. My view is that the focus should be on reading at primary school. And it doesn’t matter what children – and teenagers – read, as long as they read. Reading should be fun, not a burden.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy Website: paulaarellanogeoffroy.com LinkedIn: paula-arellano-geoffroy |

Award-winning literary translator Susan Massotty has been an active member of SENSE ever since its founding in 1990. Susan is not only known for her 1995 translation of the Definitive Edition of Anne Frank’s ‘Diary of a Young Girl’, but also for her translation of works by Dutch authors as Kader Abdolah, Cees Nooteboom, Abdelkader Benali and Margriet de Moor. Susan won the Vondel Prize in 2007 for her translation of Abdolah’s novel ‘My Father’s Notebook’. In the following interview, she generously shares stories with us about her beginnings, her connection to Anne Frank, and her exceptional career as a literary translator.

Award-winning literary translator Susan Massotty has been an active member of SENSE ever since its founding in 1990. Susan is not only known for her 1995 translation of the Definitive Edition of Anne Frank’s ‘Diary of a Young Girl’, but also for her translation of works by Dutch authors as Kader Abdolah, Cees Nooteboom, Abdelkader Benali and Margriet de Moor. Susan won the Vondel Prize in 2007 for her translation of Abdolah’s novel ‘My Father’s Notebook’. In the following interview, she generously shares stories with us about her beginnings, her connection to Anne Frank, and her exceptional career as a literary translator.

You are originally from California’s San Francisco Bay Area, but you’ve lived in the Netherlands for many years. Can you tell us what brought you to the country and why you decided to stay? How easy or difficult was it to absorb the local culture and learn Dutch?

Love brought me to the Netherlands via a roundabout route: I met my future husband on an Israeli kibbutz. We then moved to the US, but after two years decided to give my husband’s country a try. We arrived in the Netherlands in the sweltering summer of 1976 and have lived here ever since. I took to Dutch culture instantly and threw myself into learning the language. I thank my lucky stars that there are a lot of similarities between Dutch and English, so that the learning curve wasn’t as steep as it might have been.

Were you always interested in literature and translations? How did you first ‘meet’ Anne Frank?

I started reading at the age of four and am still a book junkie. It never occurred to me when I was growing up that I would one day be a translator – and certainly not when I first read Anne Frank’s diary as a teenager. Although I arrived in the Netherlands with little work experience, I landed an editing job at the Delft University of Technology, which eventually evolved into technical translation. I wanted to translate literature but didn’t know how to go about it. A literary agent I knew fortunately steered me in the right direction and helped me get my first literary assignment. Since she was also the agent for the Anne Frank-Fonds in Basel, she suggested a few years later that I submit a sample translation of the diary to the US publisher, who was planning a new edition. I was speechless when they actually approved my sample and asked me to translate the rest of the diary.

Your translation was published in 1995. Can you tell us why a new translation was thought necessary at that time?

Owing to a shortage of paper in post-war Europe, the first 1947 Dutch edition of the diary was necessarily short. Translations into other languages, like the 1953 translation into English, were of the same length. But by 1995 the diary had become a modern classic, paper was in abundance, and publishers felt it was time to offer readers more material (and coincidentally safeguard their copyrights). In the interim the language had also become a bit dated, so the US publisher was keen to have it freshened up and to have the diary translated, for the first time, into American English. Later I worked together with Penguin Group to anglicize my translation for UK readers.

I understand that you knew the late Barbara Mooyaart-Doubleday, who first translated the diary into English and was also a member of SENSE. Can you tell us about this encounter?

I didn’t want to be influenced by earlier work, so I carefully avoided getting in touch with Barbara or reading her translation before I started on mine. But when I was finished, I thought it was only polite to contact her and let her know that a new translation was on the way. She graciously invited me to her home, and the two of us hit it off immediately. She showed me the handwritten first draft of her translation, talked about her meetings with Anne’s father and explained that she had only been able to work on the translation when her three small children were taking naps or in bed. Barbara and I met many times after that and kept in touch until her death in 2017 at the age of 97.

Anne Frank’s diary is the most famous account of life during the Holocaust and has been read by millions of people and translated into more than 70 languages. In one passage, Anne says, ‘I don’t think of all the misery, but of the beauty that still remains.’ Having to immerse yourself so deeply in the text must haven been a profound experience. How did it affect you?

The diary is such a high-profile book that having to be the voice of Anne Frank was both a privilege and a terrifying responsibility. I felt I had to get things right, for Anne’s sake as well as for her readers. This meant total commitment. Or perhaps obsession is a better word. During the six months I worked on the translation, my life went on as usual, and yet part of me seemed to be living alongside Anne in the Secret Annex.

It’s easy to understand the huge technological differences of doing translation work in 1995 versus today, but can you walk us a bit through the challenges and rewards of translating Anne Frank compared to your more recent works?

In that pre-Google era, doing research meant going to the library as well as calling on the expertise of others. I’m still amazed at how eager total strangers were to help me: the BBC who sent me the entire transcript of Eisenhower’s D-Day speech, the dentist who explained what a root-canal procedure was, the doctor who discussed the effect of valerian drops on adolescents, etc. Nowadays facts like these are a few clicks away, which has made research a lot easier, though connecting with people was a much more satisfying experience.

Similarly to what fiction editors must do, literary translators need to allow some space to transmit not only the words, but also the essence and the meaning. What would you say are the most important skills a literary translator should cultivate?

First and foremost, literary translators must be able to write well in their own language. They also need to be aware of the literary traditions and trends in both source and target languages so that they can see the work they’re translating in its proper context. My advice to aspiring literary translators is to sharpen their writing skills and to read, read, read.

May I ask what you’re currently reading? Can you recommend a few books?

I’ve reached the age at which I enjoy re-reading old favourites, though contemporary works fill my bookshelves as well. My current reads include an eclectic range: everything from thrillers (Laurie R. King’s ‘Back to the Garden’) to non-fiction (Merlin Sheldrake’s ‘Entangled Life’) and fiction (Andrey Kurkov’s ‘Grey Bees’). To anyone wanting a firsthand look at literary translation, I heartily recommend Daniel Hahn’s instructive and hilarious ‘Catching Fire: A Translation Diary’.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy Website: paulaarellanogeoffroy.com LinkedIn: paula-arellano-geoffroy |

Our SENSE Summer Social began on 12 August in less than perfect circumstances – a heavy summer rain shower meant that our 17 attendees arrived wet and bedraggled, shaking off umbrellas and removing waterproof layers. Nevertheless, spirits were high, and everyone was excited and curious to see how the day would unfold!

It wasn’t long before our tour guides arrived, and we assembled at the beautiful Pandhof monastery garden of the Dom Church in Utrecht. A story was unveiled to us by our knowledgeable guides, a tale which spanned 2,000 years of Utrecht history. Large maps and diagrams were used to illustrate the ways in which Dom Square has changed over the centuries, and how it has always been the ‘beating heart’ of Utrecht. New buildings were constructed on the remains of old ones, leaving a rich archaeological legacy in the ground beneath. We discovered that the Romans came to Utrecht (which was known to the Romans as ‘Traiectum’) and constructed Castellum Traiectum in the first century. We learnt about the thriving Middle Ages of Utrecht, with its trade routes and connections via the Rhine River, and we were told how the Dom Tower came to be a free-standing tower due to the destructive force of the Great Storm of 1674.

Armed with this knowledge, it was time to venture into the subterranean depths! Like amateur archaeological sleuths, we were each given a ‘smart flashlight’ and then descended underground, ready to explore. The flashlight was attached to an earpiece and, when pointed in the right place, a voice in the earpiece revealed snippets of history about the inscribed pottery, brooch pieces and other historical remains that could be found hidden in the near darkness.

Armed with this knowledge, it was time to venture into the subterranean depths! Like amateur archaeological sleuths, we were each given a ‘smart flashlight’ and then descended underground, ready to explore. The flashlight was attached to an earpiece and, when pointed in the right place, a voice in the earpiece revealed snippets of history about the inscribed pottery, brooch pieces and other historical remains that could be found hidden in the near darkness.

We were busy searching for clues when a thunderous sound filled the room and the caverns’ walls sprang to life, showing an animation of the Great Storm of 1674. The storm had been so fierce that it destroyed the nave of the cathedral that joined the tower and the church. These parts were never connected again, and are now separated by the Dom Square.

It wasn’t long before our exploration was over and it was time to climb out of the darkness, back to the land of the living. We emerged from the ground, squinting like moles in the sunlight, and were delighted to see that the rain had passed and the sky was blue.

Having worked up an appetite, lunch beckoned. As we walked to the restaurant, we were delighted to see a bronze marker below our feet, marking the ancient boundary of Castellum Traiectum. At night, a line of steam and coloured lights emanates from this boundary. Unfortunately, at 12:30 on a sunny August afternoon, we were not able to witness this spectacle.

We arrived at Ubica restaurant, where a private room awaited us along with a delicious buffet of sandwiches, salads and desserts. After being stuck in the depths for an hour, everyone was eager to catch up and have a chat, and the room was filled with noisy chatter and laughter.

During the lunch it was great to learn a bit more about the experiences of other SENSE members, to find out what people do, both in their language work and in their daily lives. For me as a new SENSE member, it was wonderful to meet new people, some of whom have been SENSE members for many years.

As SIG & Social Events Coordinator, this was the first event that I’d organized, and I was delighted that the day was a roaring success. The tour was a fascinating insight into the history of Utrecht, and the ‘smart flashlight’ turned the DOMunder experience into a fun adventure!

|

Blog post by: Becky Tomas Website: bexchecks.com LinkedIn: bexchecks |

Freelance writer, journalist and media instructor Dara Colwell joined SENSE a few months ago. I invited her to share her interests and stories with us, and to talk about what moves her in life. Her answer was as expressive and engaging as the ones that follow in this interview.

Freelance writer, journalist and media instructor Dara Colwell joined SENSE a few months ago. I invited her to share her interests and stories with us, and to talk about what moves her in life. Her answer was as expressive and engaging as the ones that follow in this interview.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and where you are from?

A professional writer for 23 years, I hail originally from Los Angeles, though I’ve lived in Europe most of my adult life. (My brother has lived in Tokyo just as long, so our parents did a stellar job instilling us with wanderlust!) I earned my Master’s degree from UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism and worked for several years as an investigative reporter at Metro San Jose in the heart of Silicon Valley. I eventually became a freelance writer, writing about the environment, politics, culture and the arts in New York City, and later in Amsterdam. I currently teach professional writing and storytelling techniques at the University of Groningen. My very first job after graduating was teaching English as a second language, so teaching comes naturally to me – especially teaching what I love: writing!

What brought you to the Netherlands?

It’s cliché but true: a Dutchie wooed and brought me here. Our story would make an excellent, unpredictable screenplay and the tagline would have to include something about persevering against all odds. I came for love, and stayed for it, and the bonus was falling in love with Amsterdam, where I was lucky to have written for (the now defunct) Amsterdam Weekly – as writing about the city’s arts and entertainment scene helped me explore it. Living in the Netherlands has given me a quality of life I couldn’t have imagined while growing up in the US and I am deeply appreciative.

Do you get on with the Dutch language?

Yes, as my partner is Dutch. I have translated several books from Dutch to English, cleaning up the ‘Dunglish’ to make the text sing. The books are ‘Becoming Whole’, about birth, death, language, karma and transpersonal therapy (yet to be published); ‘The White Field’, about a life lived in Tibet 3,000 years ago (yet to be published); and ‘Free Up and Play’, originally conceived in English but later published in Dutch, about overcoming stage fright using non-violent communication (NVC).

Can you describe your current professional activities?

Besides teaching professional and feature writing, I am currently helping a client conceptualize, write and edit a book about effective leadership in today’s business world. I generally take on diverse writing and editing projects, from revising websites to writing articles about corporate wellness. Everything interests me, though the more creative, the better.

What are your hobbies? Can you recommend some books?

Cycling, cooking, making collages, gardening/permaculture, immersing myself in nature, and writing screenplays. I am a history nut and currently revamping a screenplay that takes place in the 1890s.

The books I am currently reading: Jay Heinrichs’ ‘Thank You for Arguing’, about persuasion and oratory techniques; Alain de Botton’s ‘The Art of Travel’, whose title is self-explanatory; and finally Paul Mason’s ‘Clear Bright Future: A Radical Defence of the Human Being’, which I just started, and looks at what being human means in today’s digitized world.

How did you hear about SENSE and why did you decide to join?

I have known SENSE for some time from fellow writers/editors. I decided to join to expand my network, learn more about who is involved, and hopefully, find more work. I am eager to network, meet fellow writers and editors to talk shop, and I am always open for job opportunities. I am full of stories and eager to hear yours, professionally or otherwise.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy Website: paulaarellanogeoffroy.com LinkedIn: paula-arellano-geoffroy |

Rachel Pierce on ChatGPT: ‘Caveats, best practices and use cases for language professionals’

Written by Susan Jenkins

On 1 June 2023, Rachel Pierce, a US-based freelance translator and copywriter, spoke to a packed Zoom meeting of the SENSE Tech SIG about ChatGPT. While many of us have dabbled with ChatGPT, it was Rachel’s recent article for the American Translators Association (ATA), ‘5 Tedious Non-Translation Tasks ChatGPT Can Do Amazingly Well’, that prompted the invitation to her so we could learn some practical ways to take advantage of this rapidly evolving technology. In the meeting, Rachel outlined how to use ChatGPT’s capabilities for tasks that can help language professionals maximize their productivity, while also acclimatizing to the inevitable changes coming to language professions as a result of generative artificial intelligence (AI) technology.

Language professionals are the most qualified users

Rachel acknowledged from the start that it’s quite overwhelming to keep up with what is happening. This technology is spurring the introduction of new tools and integrations every week. But she emphasized that ‘As linguists, we’re uniquely qualified to assess how good the tools are, and to find unique ways to use them.’ We’re encouraged to jump in and start testing their limits. A lot of the tools we use every day like Microsoft Word have incorporated AI functionality already. Think about Microsoft Editor or the auto-complete feature. Rachel mentioned Microsoft 365’s new digital assistant, Copilot. This is a ChatGPT-powered interface that Microsoft is integrating into its Office applications this year. Translators have been using machine translation tools that incorporate AI technology for several years. Following the launch of ChatGPT, many professionals are now looking at how they can incorporate new AI tools into their language-related workflows. As Rachel says, ‘It’s coming whether we want it to or not.’

Tools that automate ChatGPT

Rachel discussed a few tools she’s been sampling that interface with ChatGPT. She mentioned Wordscope, a web-based multi-functional translator’s toolkit that uses buttons to interact with ChatGPT and send it pre-written prompts for various tasks. Gaby-T is another app built to automate ChatGPT interaction for language professionals. These are but two of many tools now available either as a plug-in within ChatGPT or as a browser app or web-based app. In short, these tools automatically generate complex prompts so we don’t have to be ‘prompt engineers’ to leverage the chatbot’s ability to process sophisticated instructions. But Rachel also suggested that it’s good to learn some prompt-writing skills, reminding us that we all learnt how to use search engines 20 years ago – ‘We’re already good Googlers, so we can learn how to talk to a chatbot.’

GPT 3.5 versus 4.0

The second half of the presentation focused on best practices, caveats and demonstrations of different tasks that applications using GPT can do. Rachel briefly mentioned some differences between the two language models currently available on the software site: GPT 3.5 is free and faster, but trained on less data so best used for simpler tasks; GPT 4.0 (subscription only) is trained on exponentially more data, so it handles complex instructions better and its responses are much more accurate.

Shortcomings

ChatGPT’s shortcomings are notable. An important one is the lack of training on data after September 2021, which limits its ability to generate responses containing more recent information. Another is its tendency to ‘hallucinate’ – to generate responses that sound true but are riddled with fabrications. For example, it is known to make up citations. Hence, a key best practice is to verify any information it reports. And because it has no privacy safeguards, it’s important to check our non-disclosure agreements before pasting anything into ChatGPT that shouldn’t be shared.

Best practices

ChatGPT performs best when given context for the instructions and also a format for the output. We must describe the purpose of the text/response desired and how long or short it should be, as well as the style or tone. And make use of the different ways to refine responses – either by providing further instructions, or using the regenerate button.

Time-saving tasks

Shortcomings aside, Rachel took us through a demonstration of how she uses ChatGPT with a dozen simple prompts. We watched ChatGPT generate its responses as she went through various scenarios that any of us might do in the course of our work, such as finding alternative/substitute words; making grammar and style decisions; comparing and contrasting at a higher level; summarizing an article, book or other text; creating and then redacting; organizing your thoughts; and clearing writer’s block.

One of the most interesting of these was summarization. Need to research a topic quickly? Rachel demonstrated how to paste in the text of an article and ask ChatGPT to summarize it into one or several key points. (Note the limits: up to 3,000 words per prompt with GPT 3.5 and 25,000 words with GPT 4.) She also used the browser with Bing plug-in to retrieve the text of two academic articles from the web for ChatGPT to summarize. The plug-in automated the retrieval, submission and summarization of all the requested articles into one command. Other big time-savers were having it organize a set of talking points for a networking event and a presentation. It also can help clear writer's block. In one example, Rachel asked it to generate captions for a dozen images of a fitness centre. It provided a list of options so she didn’t have to come up with a dozen on her own. These are a few ways ChatGPT can help writers get ‘creatively unstuck’.

Further inspiration

The results were impressive and gave many of us new ideas to experiment with. We appreciated her key takeaways for language professionals in navigating this moment:

- Clients are also overwhelmed – it’s a good time to start a conversation with them about their AI plans.

- Stay on top of how your preferred tools are incorporating AI – follow their companies, and take advantage of the free webinars that are happening.

Questions and comments were diverse, from ‘What is it doing when it regenerates?’ and ‘Why does it hallucinate?’ to whether the output generated can be detected by plagiarism checkers. One academic copy-editor asked whether it really saves time if we have to check the accuracy of everything it generates. Perhaps the best answer is the well-known adage ‘user experience may vary’, but as language professionals, it’s important to understand both the capabilities and shortcomings of the tools we use. Especially when they are changing the landscape in which we are working.

|

Blog post by: Susan Jenkins Website: stjenkins.com LinkedIn: susantylerjenkins-connect |